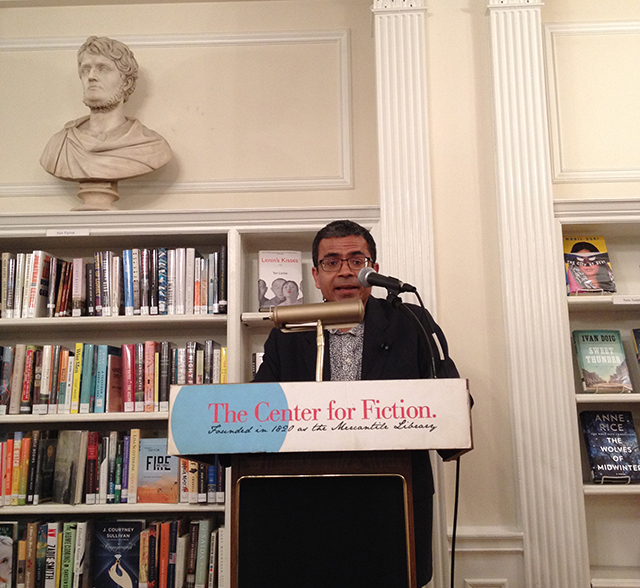

Twelve and a half years and seven thousand pages later, Akhil Sharma’s second novel, Family Life, has been released to rave reviews from places like The New York Times. George Packer, staff writer at the The New Yorker joined Sharma at the Center for Fiction to discuss the novel, a fictionalized, semi-autobiographical account of Sharma’s early life.

The soft-spoken Sharma begins by saying he doesn’t read reviews largely because he can only ever focus on the negativeness, no matter how minor. He’s hypercritical of himself, evident both in his demeanor and his novel. He also worries that if he begins reading book reviews, he will then only write for praise rather than for what he believes to be good writing.

The novel takes shape from Sharma’s own life. As the jacket of the novel suggests, his brother actually did end up injured in a childhood accident. The accident left Sharma’s brother incapacitated. After two years in hospital, his parents moved their injured son into their care at home. “They loved him so much they didn’t know how to show their love,” Sharma says. Taking care of their injured son themselves seemed the only appropriate way to express that love.

Despite the links to biography, Family Life is a novel. “I’m a fiction writer. I know how to use the tools of a fiction writer,” he says. He avoided memoir because of the limitations of the form. “You can’t just make shit up.” Much of his actual childhood was boring he says. “I have no desire to write about boredom.”

The Sharma family immigrated to the United States from India in the 1970s, a time before Indian immigration was commonplace. The family settled in central New Jersey partly because that was one of the nascent Indian communities in the country. Partly he wanted to capture those experiences. “Ordinary people get forgotten,” he says. He wanted to memorialize the community by capturing some of the aspects of life as an Indian immigrant.

Family Life focuses on a dark personal experience–shame, fear, guilt. The same is true of his first novel, An Obedient Father, a book with a child molester as a protagonist. But throughout both texts, Sharma finds humor. “I have a hard time not finding absurdity,” he says.

As he reads, Sharma interrupts himself to offer commentary. The effect feels something like a cross between DVD bonus feature and a lecture, but the wisdom of a seasoned author and writing professor seeps out. The opening scene exposes Ajay’s parents having a disagreement. “You always want to begin with a fight,” he says. The promise of a fight allows the author to bring the audience into the world and then the author can get weird, he adds. Sharma says he likes to combine lovely things with gross things. He places them side by side.

The characters in Family Life are more appealing than in his first novel. In An Obedient Father, the characters’ flaws cause the reader to want to pull away from the text. To keep the reader engaged, Sharma says he linked paragraphs tightly together with small cliff hangers. In Family Life, he felt he could leave the paragraphs more open because the reader empathizes with the characters.

Sharma is very concerned with balancing the quantity of certain types of sentences–exposition and plot and setting all need to come together in the right proportions. He explains that his goal is to turn exposition into poetry or humor to ease the burden on the reader.

After reading, he and George Packer begin a discussion of the book. Packer asks about the different versions of the text–Sharma read from the excerpt printed in The New Yorker rather than the novel.

The short story as a form, Sharma explains, has different requirements. The novel has a higher tolerance in duration and gains the sense of artfulness gradually. The short story as a form requires more polish to achieve that same sense. He explains that he removed the repetition of words in the story version to help keep it succinct. His protagonist Ajay discovers Hemingway’s use of repetition of words, and the reflection of this in the novel shows the verisimilitude.

Packer asks why the novel began as it did–the narrator reflecting back, rather than structuring the novel like a Bildungsroman or begin at the moment of the accident.

In the seven thousand pages and multiple drafts, Sharma says, he experimented with many different ways to start and tell the story. The important thing is he wanted a narrator with more complicated diction than a child would have. By having an older narrator look back, he could use sophisticated language and still have a first person voice. Second to that, it allowed for the novel to traverse great pain. The reader knows that the narrator has survived thus diminishing whatever hardship he is put through.

Most novelists begin with an autobiographical novel and then the follow up novels rely on more inventive plots, Packer says. Why then did Family Life come second.

The plot is not the thing that is autobiographical with the first novel. However, Sharma sees it as emotionally autobiographical. Even though An Obedient Father contains fictional characters, the feelings of pain and guilt and hurt all existed. The child molesting protagonist experiences similar feelings of isolation. Sharma felt survivor’s guilt, pain that his brother was injured rather than him. “How do I convert that into fiction reality?”

Second to that, Sharma adds, is that he felt very ambitious. He wanted to signal to the world how great a writer he was, and the best way he felt to do that was to write an ambitious novel.

Finally, to write Family Life, a novel that took more than a decade, he says he required a greater feeling of tenderness. Partly that feeling came with time. Partly that came from writing his first novel.

Packer asks if that empathy came from his decision to begin praying, outlined in The New York Times.

Sharma, who does not believe in God, began praying several years back. It was a tip he found in Reader’s Digest— praying for other people’s happiness. “It allowed me to think about someone other than me.”

The years of writing the novel also allowed Sharma to develop a precise text. He has winnowed away whatever detritus existed in the early drafts. The first thing was that he left behind the third person. The first person novel and the third person novel consume plot at a different rate he says. The first person voice puts the character at risk. He’s written drafts of the novel both ways. He also wrote it from the perspective of the mother and then from the father.

Over the course of editing, he dropped chapters, like one on the father’s alcoholism. One way that Sharma edits is by starting over. He begins with a blank page and writes from scratch leaving out the things that are unimportant to the text. His goal is to get to the point where only the most necessary elements are left in the story. With non-fiction, leaving out facts is sometimes impossible or misleading.

Sharma is often lumped in as an immigrant writer. Seven years ago, he even ran with a gang of “immigrant’ writers in Brownstone Brooklyn. Packer asks him if this designation bothers him.

“When I was younger I resisted that term,” he says. He wanted to be known simply as a writer. Now though, he adds, “as you get older, you realize you always have to deal with idiots.”