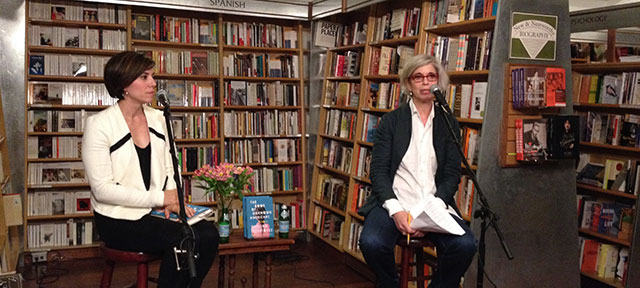

Cristina Henríquez’s latest book, The Book of Unknown Americans (June 2014), focuses on the lives of a group of immigrants residing in Newark, Delaware. A cast of eleven voices comes together from various Central American nations as they acclimate to life in the United States, some legally, some with more questionable circumstances. She was joined at McNally Jackson by her editor Robin Desser for a conversation about the book.

Henríquez says she didn’t set out to write about immigration. “Immigration to me is a system, a political reality that is complex,” she says, but by itself, its not all that compelling a topic for a novel. She wasn’t interested in the technicalities as much as the people and their lives.

Her father came from Panama to the United States in 1971. For him, she says he retains the sense of otherness in the United States, yet he no longer feels like he fits in when he returns to Panama either. It was this anxiousness she wished to capture.

The novel began with twenty different speakers all offering their own stories. Her editor convinced her to reduce the number down to the eleven that made it into the book. She kept separate files for each speaker, and another for the main story arc.

“I have all these voices in my head actually,” she says. Cutting characters wasn’t easy. Some she combined into one person, preserving the essential characteristics, but others she had to let go.

Some of the characters have traditional immigrant narratives. One speaker for instance, arrives in the United States illegally having paid a bounty to a “Coyote” and then works selling drugs to pay off his debts. Eventually he becomes hooked, only to escape to Newark. Others are more unexpected, like a theater troupe operator.

The novel is intentionally set just as Obama ascends to the Presidency. He looks different from the other preceding Presidents offering the characters hope. His otherness serves as a reminder of possibility.

Food plays a major role in the novel. Its the one aspect of culture that can travel with people who migrate. And yet food also offers a certain kind of culture shock though. One of the families in Henríquez’s book discovers American oatmeal. She reads a passage about the mistakes made cooking it the first time. The discovery of the cheap food at first excites the character–so inexpensive, and yet so much. But the oatmeal is cooked too early and turns to a rubbery blob before they eat it. Its a moment of both disappointment and awe. Desser says its one of the scenes that convinced her that Henríquez’s book should be published.

Desser says that when an editor reads a manuscript for the first time, there is a visceral memory of the manuscript. In Henríquez’s book, the tension of families resonates.

Henríquez says that she even though she isn’t an immigrant to the United States, her family traveled around a lot as she was growing up. That kind of dislocation generates a similar unease and a desire to have a sense of belonging. Though the details of her novel are of Latin American origin, the experiences offer a universal look at outsiders and otherness.

Henríquez’s mother works a translator in a school district in Newark, Delaware. She works with disabled children of Spanish speaking families. It was those experiences, and the idea of highlighting this community, that inspired the novel.

Along with the book, Henríquez has launched a tumblr, UnknownAmericans.Tumblr.com, to tell immigrant stories. Individuals write a four hundred-word piece and send in a picture of themselves. The idea is to highlight these otherwise untold, ordinary stories of immigration.

Henríquez wants to figure out ways of putting real life into novels. She draws inspiration from many different places. “If you looked at my Google history, you could tell the next book I’m going to write,” she says. Some of her her work draws on personal experiences. “I was an angsty, journal-keeping teenager,” she says, saying also that reading those sometimes leads to a depressed spiral of nostalgia.

When it comes to specific research, she only did a little. She says she wanted enough fact to accurately portray the different cultures of the characters, but too much research can hamper the imagination.

In school, Henríquez says she was very disciplined. She set alarm clocks to write early in the morning. Later, she worked at a movie theater and would write out notes during the down time. She was always squeezing in time to write. When she had children though, all that changed. Eventually she realized she could hire a babysitter. She credits her husband for acknowledging that her work was just as important as his. Now she says she writes for about ten to twelve hours a week.

Desser adds that she has never missed a deadline.

Cristina Henríquez and Robin Desser

Monday, June 11, 2014

McNally Jackson Books