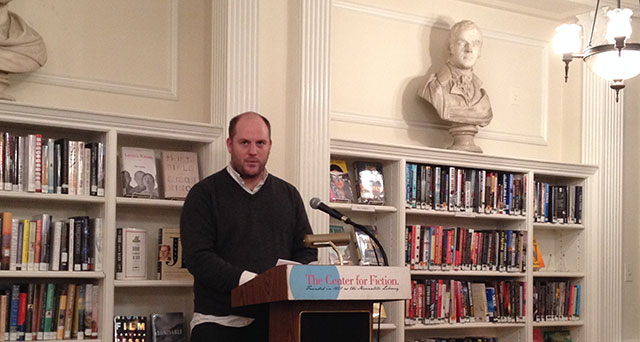

The Center for Fiction hosted authors Adam Wilson and Peter Mountford for a reading from their new books and a discussion between them. Wilson’s collection of stories What’s Important is Feeling will be released next week while Mountford’s novel The Dismal Science was released in January.

Mountford is the author of a previous novel, A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism (2011), the story of a young hedge fund analyst sent to Bolivia. Both novels began as one book that he cleaved apart. The two competing stories failed to mesh together, with the The Dismal Science following Vincenzo D’Orsi, a vice president of the World Bank. Mountford read an awkward sex scene between Vincenzo and a middle-age woman.

What’s Important is Feeling is Adam Wilson’s first collection of stories, but he also has a novel Flatscreen (2012) about a misunderstood narrator struggling to mature into adulthood. He read the story “The Long In-Between” about a young lesbian moving to New York to live with her former professor; Wilson prefaces his reading by saying he normally reads to drunk audiences who forget that the narrator is a young woman.

After reading, the two novelists sit for a discussion of their books beginning with the role of workplace narratives. Work holds a prominent place in The Dismal Science. As a vice president at the World Bank, Vincenzo’s narrative dances around the bureaucracy of an institutional workplace and global economics. Wilson’s characters have a different approach. His narrator in Flatscreen wouldn’t even know how to find a job, let alone hold one. And in his story, “December Boys Got It Bad,” two bankers suffer the antithesis of workplace novel–laid off from their jobs, they set off to Brooklyn hoping to pick up young hipster girls.

.jpg)

But work is an important part of people’s lives, Wilson says, even if often in literature jobs are nonexistent and characters end up being classless.

Mountford describes the classless character as antiquated. He says its too much like John Updike setting characters in the suburbs and allowing them to seethe in their own middle-class neurosis.

The middle-class means many things to people, Wilson adds. There are many different levels of middle-class. Often there is this struggle up and down within that middle. He also describes it as a very American idea.

Money in literature is often either represented in the way that Bret Easton Ellis shows it–nihilistic consumption–or on the opposite end of the spectrum, poverty leading to a life of quiet desperation. There is, in literature, something sexy about not having money, Wilson says.

Jobs are very much a part of people’s lives, Mountford explains. And maybe, he suggests, there is a kind of need for escapism in literature.

“People love the narrative of: very rich people are corrupt and then pay for it down the line,” Wilson says, adding that it’s kind of a romantic notion.

A character’s comeuppance is an important component of plot, but characters also have to have a kind of likeability too. Mountford explains it as “rehabilitating the monster.” Showing the character’s humanity is the primary way a reader cares about a character. Sometimes, a character ends up making a choice that the reader doesn’t like, but the character’s faulted humanity allows the decision to be palatable.

Wilson agrees that this is the challenge to creating unpleasant characters. “People don’t need to like a character, they just need to want to spend time with them.”

One frequent criticism of Flatscreen is that the narrator is unlikeable. “I find it hurtful,” Wilson says, because he sees the character as himself.

Everyone hates bankers, Wilson says, but how do they end up the people everyone hates? “You want to surprise your reader,” he says; no one expects a banker to cry while looking a Rothko, as one of his bankers from “December Boys Got It Bad” does.

Wilson primarily writes in the first person. One challenge with this perspective is crafting dynamic world through the character’s voice, because everything ends up filtered through the narrator, and is particularly challenging with characters who are described as unlikeable. His advice is to not condescend to the character.

Mountford offers a different concern. He writes primarily in third person perspective, allowing him to move closer and farther from his characters as necessary. Vincenzo though is a character who is a little bit anti-feminist and Mountford worried readers would confuse his words as a writer with his words as the narrator.

He also adds that Vincenzo is a somewhat more eurite version of his father. Mountford’s father was also an economist who worked at the IMF. Mountford, like his father, has a background in economics. He even worked in finance for a brief moment until he “felt really dirty.” But ultimately these characters and their muses are distinct beings, but there is always a kind of worry about how readers perceive character, voice, narrator, and author.

Wilson’s father is a writer. His big concern was reading his father’s books: “I didn’t want to know how he imagined a sex scene.” He flipped that on his father though. In Wilson’s story “Milligrams,” a lobster is used as a sex toy. He read the story when he graduated with his MFA where his parents were in attendance.

Adam Wilson and Peter Mountford

Center for Fiction

Thursday, February 20, 2014