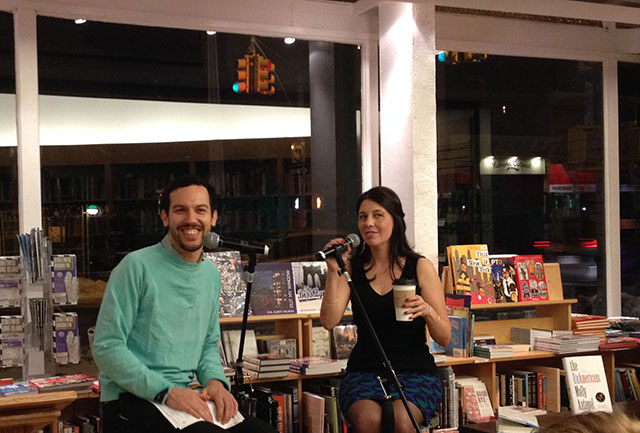

Molly Antopol, named one of the 5 Under 35 by the National Book Foundation in 2013, released a collection of short stories, The UnAmericans, earlier this month. She read from the book at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn with Justin Torres, author of the novel We The Animals.

Antopol reads a portion of a story about a young journalist and her encounter with a widowed man. Many of Antopol’s characters have the sort of profession that allows them to observe their world, like journalists or writers.

Torres begins by asking about the scope of the book and the reasoning behind the UnAmericans.

Early on, Antopol says, there was an element of McCarthyism to the stories, and to her relationship to that. But the book took ten years to write and evolved. Partly these stories address Antopol’s fascination with the relationship between Americans and Israel, and partly she wanted to explore these characters who spent their lives fighting communism and then suddenly find themselves in a place where they are not surveilled, or not even noticed.

The stories are set across Eastern Europe and Israel and the contemporary United States, but even confined to these places, the narratives traverse time and space. The globalism of the narratives and the broad scope of time comes from Antopol’s interest in generating the details of her characters’ past.

“I love backstory,” she says. She also says that in creative writing workshop, as a student, she was taught to focus on single scene stories, to contain a stories time and place. But for her its difficult to explore the world she created without adding in that backstory.

She looked at writers like Alice Munro and Edward Jones who she sees as putting every part of themselves into their stories. Each story Antopol writes takes about a year.

Torres observes that he finds the notion terrifying — that starting over in a new world each time after dedicating so much to each would be frightening.

For weeks after finishing a story, Antopol says, there is a period of feeling sad as the world she has created has finally come to an end.

Many of her characters live in intentional communities, or are seeking them out. They avoid, what Torres terms, the messiness of families. His novel, We the Animals, by contrast, embrac

es familial messiness.

“All of my characters are lonely because life is lonely,” Antopol says.

She lived in a commune for a while, an organized, intentional community. But ultimately, she says, she felt too selfish to thrive in those kind of shared spaces. But her characters are perpetually seeking or escaping people.

Though she has spent some time in organized communities, the stories themselves are not at all autobiographical. Some of the basic concepts might have origins with people she knows or family, but once she begins imagining a world, the fiction takes over.

Antopol says too that its hard to escape characters as observers, like having writers as characters. With creative writing instruction, there are a many don’ts. She was told not to write about writers, not to write about sex, not to write about dreams. But, she says, its annoying to have someone tell you what to do.

“I love research,” she says, like the “itty bitty details.” The things that writers obsess about are the elements that make a book unique to that writer. But she also wanted to avoid writing stories that felt as though they were historical fiction, and the easiest way to accomplish that was to place those stories into the voice of characters.

Antopol has been compared favorably to Jewish writers like Philip Roth and Grace Paley. She embraces the comparisons. But Torres asks her if she’s concerned about becoming pigeonholed as a Jewish writer.

“I don’t think I can escape it, I’m just so Jewish,” she jokes. She says that while she doesn’t want to be labeled in these sort of categories, it is impossible for her not to also be a Jewish writer, or a woman writer. In the case of her stories, it is partly her way of understanding her parents’ experience with the Soviets, and her own relationship with that. Its impossible for her to escape writing about these topics.

Place often informs plot, Torres notes, asking about the relationship of the stories to Israel and the United States.

The most difficult stories to write, Antopol says, are those set in contemporary America. In Israel, she always has a feeling of being an outsider and observer. She has traveled through Eastern Europe, too. In new places, everything is an experience, but in the United States, because she lives here, the routine is more difficult to observe.

Antopol says she writes regularly like its a job. It is. She doesn’t sit around waiting for inspiration to strike, because it never would. All you need is a laptop, she explains, and because she travels, she often finds herself writing while on airplanes. She says she tries not to be “precious” about writing or caught up in a particularly routine, because then she would never write anything.

“I don’t know how to write a short story,” she says, and then adds that every time she writes one, its like learning to write it all over again. She’s currently working on a novel. All she says about it is that its set in Eastern Europe, Israel and New York. She also adds that she’s never written a novel before. The main thing she has noticed is that in the novel, she has plenty of room for the backstories she enjoys.

Antopol teaches creative writing in California. She says that even if she didn’t need to teach, she probably would continue to. It gets her out of the house, it makes her read more, and because she is teaching, she keeps up on contemporary writing.

Torres, who also teaches creative writing, disagrees. He says there are good things and bad things about teaching, but mostly he thinks that creative writing workshops end up leaving him solving the same sort of problems.

Antopol says she enjoys that element because solving her students’ problems offers the kind of illumination she never finds in her own writing. She also teaches writing for radio, and that has influenced her cadence, structure, and narrative voice.

Antopol also reads a good deal of poetry, particularly when she revises her writing. She says she avoids fiction and non-fiction during the revision process because she fears the influence of other prose on her own voice. Poetry also demonstrates alternative narrative structures, and those differences she finds exciting.