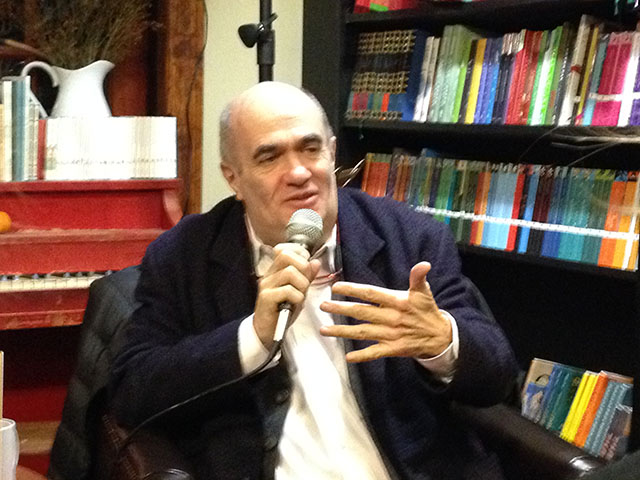

Rabih Alameddine debuted his new novel, An Unnecessary Woman, at Community Bookstore in Park Slope and conversed with Colm Tóibín on Wednesday. Tóibín is the author of The Testament of Mary (2012), a novel exploring the life of Mary, mother of Jesus, and he is a professor at Columbia University.

Of Lebanese ancestry, Alameddine was born in Jordan, raised in Kuwait, educated in Britain and California, and now resides in San Francisco and Beirut. He speaks Arabic, English, and French. He has written five previous novels.

An Unnecessary Woman is the story of a 72 year old woman living alone, slowly translating books into Arabic. Alameddine reads a short portion of the book following a moment when she has accidentally dyed her hair blue, before Tóibín begins asking questions.

First though, Tóibín looks first to Alameddine’s bright yellow shoes and asks him about them. Alameddine proudly shows them off, declaring he has two other pairs in hot pink and red. They are manufactured by the German company, Atheist Shoes. “They look fabulous,” he says, showing off the souls emblazoned with the brand name. In the United States, early shipments of the shoes began disappearing until the company removed the name from the box. Alameddine displays them proudly as much for their style as their message.

Tóibín next asks Alameddine to talk about class and culture in Lebanon, and to describe his own upbringing. “Who are you?” he wants to know, who was your father, your grandfather.

Alameddine jokes that these are the same questions the Australian’s asked for their visa application. His father was born in Caracas, Venezuela; his mother in Jerusalem. But these points of origin are not important to the Lebanese. “It doesn’t matter where the hell you were born. Its about heritage,” he says. He describes his family as an old one; they can trace his family back to 600 c.e., but though they are an old family, he says, they are not a great one.

His family was titled until 1710, meaning they owned land under the Ottoman Empire. For a period they were also princes, and Alameddine jokes that he’ll respond to Prince or Princess if someone calls him that. Now, he says, most of his family drive taxis.

He grew up in Kuwait. There was nothing but desert, meaning Alameddine had plenty of time on his hands to read books. His mother mostly had novels from the bestseller list, because those were available there. He became a big fan of those kinds of books for a while.

At home, his family mostly spoke Arabic. This decision was a conscious effort by his father to distance the family from bourgeois values. In Lebanon, the middle-class mostly spoke French. Though he can speak it, his father believed in the Pan-Arab movement, and Arabic provided an important component to rejecting western culture. His father wanted his family to speak Arabic at home.

Tóibín asks about Lebanon as a cosmopolitan place.

Beirut is both cosmopolitan and backward, Alameddine says. “If you consider sophistication woman walking around in thongs–” he offers, and yet across the street might exist a neighborhood where the women cover their heads. There are western standards in one neighborhood, and literally, across the street, as conservative as Pakistan; nude beaches coexist adjacent to beaches where women swim fully clothed. He also describes a city filled with people who never leave their enclaves. As an example, he says someone living in the Upper East Side might never have been to a neighborhood as nearby as Chelsea and possessing only some basic knowledge and rumors of these other neighborhoods.

People of Lebanese heritage live around the world, and Alameddine credits this diaspora with keeping the Lebanese economy afloat. He explains that older generations buy property in Lebanon hoping the younger people will one day return. The expats send money home. Still, a global presence does not come without conflict. In places like Australia, being called a “Leb” is a slur.

Lebanon has not been without its high and low points, including several wars, and Tóibín asks when Alameddine considers the best times in Lebanon.

Alameddine says that for him, the best year was 1975, at the start of the war. It wasn’t so good for Lebanon. But for him, it was a great year. He began discovering his sexuality. He had older boys playing guitar for him in their underwear. He was really into Bowie.

When it comes to politics, Alameddine is absolute: “I hate all politicians, just despise them.” While he was growing up, his father was anti-fascist, and anti-Israel. There always seemed a reason for Israel to attack Lebanon.

When it came to religion, Alameddine makes clear that his shoes are not just fashionable. He’s an atheist. But he also was raised as Druze, a religion he describes as having its origins in Islam, but moved so far from it they are declared heretics. Plato is a prophet. There are no priests or clerics, or even churches for that matter. They are unifiers of religion. Life is for learning. God doesn’t have a problem if had sex with the entire Arsenal team. In his next life, he would learn to do better.

Given Lebanon’s conflicts, especially the civil war, Tóibín asks Alameddine when he escaped.

“I escaped really early by reading. It was my one true escape,” he says. But physically, he left at the start of the war. He was sent to boarding school in England, though he says this was worse than the war itself. He was not treated well in 1970s England. He says the are English racists and pigs. In England, he wasn’t allowed to join a soccer team, a sport he enjoyed. But he did continue his education. “I Learned Thomas Hardy,” he said, “I didn’t understand how a culture that produced Hardy could produce these pricks.”

He also learned to huff glue, and when he set off for university, he smoked a lot of weed. Alameddine says his grades suffered, and warns that drugs do mess things up. But, he adds, you should try them.

The idea for An Unnecessary Woman existed for “quite a while,” Alameddine says, adding that Tóibín’s Brooklyn (2009) helped him to see how it was possible to achieve the story that he wanted. Both books are about making the everyday experience sublime. His character was the most important aspect. She had to be perfect. She had to achieve both a uniqueness and universality.

“The book is political, because everything I do is political,” Alameddine says. He also adds that sometimes its easy to feel a sense of rage that someone like Lady Gaga is widely known in the world, but more cerebral people are not.

Writers often find metaphors for themselves, Tóibín says, and that reading is strange, sad, and solitary, that often writers live in a world where its people like Lady Gaga versus them.

Alameddine considered that many readers assumed things about him based on his other books. But An Unnecessary Woman is by far the most autobiographical work, even if the protagonist is a woman. “I used to think I would have to be truly fabulous for people to think I’m wonderful,” he says.

Alameddine is not just a writer. He says he is also a book collector and often buys hardcopy books even if he has a paperback. He intends on donating his personally library to his hometown in Lebanon.

When it comes to process, Alameddidne says that he doesn’t plot out his books. It works for some writers, but not for him. “I never know what I’m doing,” he adds. An Unnecessary Woman started initially as the story of a widow claiming her husband’s body from Kuwait following the first Iraq invasion. The only thing that ended up in the final novel was the idea of using an older woman.

He says that as a writer, the it should be the easiest thing to inhabit the voice of someone else, of a character. That is what writing is. But what he wanted to do was explore the idea of exile on a person. The challenge was coming up with the right person to confront this issue. Ultimately the character had to be a woman, and not a gay man. He rejects the romantic notion that writers’ characters take on a life of their own and drive the story. He thinks it is a silly idea. “Voice is part of the structure,” he says, “once you get it right–its right.”

Alameddine wasn’t always a writer. He started out as an engineer. He says educated Middle Eastern men had two choices: becoming an engineer or becoming a doctor. For those who weren’t very bright, they went into business. Alameddine became an engineer, a profession he practiced for four months. He says he was good at math in school, and good with solving problems, but he was a mechanical engineer. In the real world, he just didn’t care enough about how things worked.

He finally got into writing after a bad breakup. He was a painter at the time. A wealthy, business-focused boyfriend, jealous of Alameddine’s creativity, decided he too wanted to practice an art. Alameddine says the boyfriend wrote an offensive story, and by the time he was an ex-boyfriend, Alameddine had committed to writing just to show him up.

“Revenge is a wonderful reason to write books,” he says.