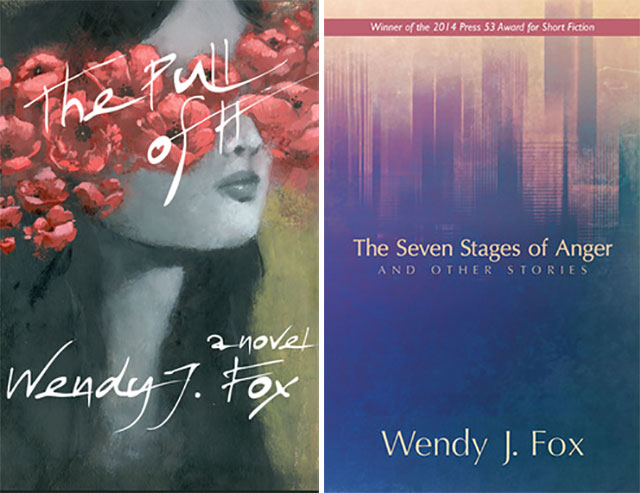

Wendy J Fox is the author of The Pull of It and The Seven Stages of Anger and Other Stories. She first met Lisa Morrow in Turkey, and for a time were both neighbors in the same apartment block. Ten years have passed, but the two recently caught up to discuss Fox’s new book.

***

Lisa Morrow: Your novel, “The Pull of It” came out in September 2016, but the story itself started much earlier. Tell us a little of your experiences in Turkey that prompted you to start writing your novel.

Wendy J Fox: I came to Turkey pretty fresh out of graduate school, taking a job in the English department of Erciyes University, with the idea of a novel looming—at the time, I thought of trying to make my way in academia, and I knew that I would need more than just a handful of short-stories published if I wanted to do more than adjunct once I returned to the United States. Really, I had less than a handful in print, just two.

I kept saying to people before I left, Maybe I’ll get a book out of this, and while I started The Pull of It sitting on the steps of my apartment in Kayseri, I had no idea the novel would take almost another fifteen years to see print.

In the first months, there were all the usual things that are challenging about new countries, like learning the transportation, or learning the polite customs, or things in a grocery store that are different; that’s the ordinary that probably doesn’t need any column space. I was lucky to have a great community around me, but writing was a lifeline.

What struck me about Turkey, in the early 2000s, was how the culture of surveillance had not yet fully arrived—there wasn’t a lot that required an ID or a credit card. Many businesses were still cash only, and negotiation was the norm. Payphones were plentiful. People changed currencies at markets, not banks, regularly. I struck on this idea that Turkey was a country someone could really disappear into: no one is really watching, and it’s easy to not leave a trail. That was the idea that took hold of the protagonist in The Pull of It, Laura.

And, I didn’t stay in academia. I’ve worked in corporate marketing since 2006.

Morrow: Did you always know from the start you were writing a novel, or did the form evolve over time?

Fox: I did imagine the project as a novel from the start, though I was completely overwhelmed by the idea of writing so many pages in succession, so I started tackling it in portions, twelve or twenty pages at a time, story-sized. So, while my intention was to write a novel, I was not writing a novel.

What this meant was that when I thought I was through with a first draft, the draft was in bad shape. I had word count, I had page count, but my “chapters” were really sorta linked vignettes with not quite enough leg to stand on their own as pure stories.

It took an incredible amount of revision to re-shape the project into something that read like a single, cohesive work, and still even after several re-writes, the book sat in a drawer. For years. I wrote another novel (still unpublished—just starting to shop it) in-between. I had a book of shorts come out. I changed the title, I read the whole thing aloud, I paid a proofreader, I begged friends to give me feedback.

I can say I learned that having an idea for a novel and having the volume of a novel, is certainly not the same thing as writing a novel.

Morrow: These days, it’s almost impossible to find a publisher without having an agent first. Did you approach any agents to represent you?

Fox: I was rejected by close to a hundred agents. I will say here that the first cut of agents were very well researched, and the final ones were an act of desperation.

Still, I got some good feedback from agents, which can mostly be summed up into two categories: 1. Nice writing—don’t think I can sell it and 2. Nice writing, but sorry, readers will hate your main character.

Morrow: When you struck out via the traditional route of agent to publishers, and decided to submit your work directly for publication, what influenced your choice of publisher/literary outlet?

Fox: There are so many small and micro presses doing great work, and I’d had a very positive experience with my short-story collection, so after giving up on agents, I decided to look for a small-press home for the novel.

Writers still have to be realistic. First of all, not every Big Five contract means you’ll be a bestseller, and not every small press contract means you’ll go out of print in a week. The landscape has changed to accommodate an incredible amount of nuance, and in shopping smaller presses, it’s about looking around at the books they put out.

Both of my publishers were very clear about what they could and could not do. Good small presses are prioritizing the words between the cover. Some are lucky enough to also have designers, a marketing person or two, perhaps even maybe a sales rep. Some are a single person succeeding by sheer force of will. The small press is largely a labor of love, and while they typically aren’t going to get you on national television, they’ll be a steward of your work, so you look for that—you look for connections, for folks who are going to push you in the editorial process to make the manuscript better. The best small presses are just as proud to see their name on the cover as you are to see yours.

Morrow: What resources did you find most useful for honing in on the best fit for your work? I’m thinking online writing groups, community resources, blogs, websites and so on.

Fox: There are very detailed resources—think newpages.com, pw.org, duotrope.com—but I frankly think it comes back to the same old question: what are you reading? I submitted my book of shorts to the press that had published one of my favorite short-stories of all time, and I submitted my novel to an up-and-comer because I liked what they were doing in terms of taking risks.

Morrow: As an Australian author I know how hard the American literary fiction and creative non-fiction markets are to crack. At times it can feel like a closed shop. As an American national, writing and living outside the New York literary scene, have you felt disadvantaged because you’re an indie author from the west?

Fox: Right, it still seems like some kind of anomaly when writers are not living in New York City, even there’s an entire modern canon devoted to this question. Even when there is a whole lot of world that is not New York.

I think it’s less of from, and more of stay.

There are absolutely many authors who have had great New York publishing success who have chosen to remain outside of the city, just are there are many who have thought New York City is the only way to make it. There’s probably some lost opportunity for people like me, perhaps in terms of access and exposure, but I don’t think, for example, that I’d have an agent just by design of living closer to where most of them are. The work I’m interested both reading and writing in seems to be less interesting to commercial publishers.

Still, you’re correct that the scene can feel closed to outsiders, but there’s also so much that is happening in metros across the US, it’s hard to discount it. There are great bookstores, great communities, and great writers almost everywhere. There’s also a kind of closeness because in the west, my hunch is that more writers are indie. I don’t have stats for it, but there’s definitely a feeling of hey, we are doing this, we are doing it together.

Morrow: Both The Pull of It and your earlier collection of short stories, The Seven Stages of Anger have been published by small presses. What has this meant in terms of promoting your writing? Have you had to be more active in drawing attention to your work by seeking out reviewers, interviewers, readings and so on?

Fox: A few small presses employ publicists; some indie authors hire them on their own.

What I think is important for writers to know is that even being on a big press means is not a guarantee you won’t be driving around with a box of books in your trunk.

Probably the biggest distinction is that small press authors are (probably) less surprised when this happens.

Of course small press writers do have to work harder for promotion; we often set up our own readings, we pitch media, we work with bookstores who won’t just order from the distributor and we put a handful of copies on consignment. It’s not ideal, but it’s often the difference between seeing a work you believe in go to print or not.

Morrow: As a self-published author I’m sometimes accused of being shameless when it comes to marketing my own work. The first time it happened I was really shocked, but then a friend pointed out that there’s nothing wrong with telling the world I’m proud of my own work. Do you think there’s a fine line between writing and marketing that a writer shouldn’t cross?

Fox: I think that’s tricky. I frequently say I’ve worked in corporate marketing for going on a decade now, so I have lost the capacity to feel shame.

Even while we keep an eye on promotion, we have to manage our own brands. If all my Facebook friends ever see from me is a call to buy something, they’ll get disengaged quickly, but I never feel weird about posting articles I’ve written, reviews, or blog posts.

Timing also means something. I had a whole series of promo posts and tweets that I’d scheduled to hit right after the US elections that I turned off because I felt like no one could possibly care (including me) about my books after what had just happened.

But, I think you are on to something that there is nothing wrong with announcing success or being proud of your own work—The Pull of It would have never seen publication if I had not believed in it as a novel, and I think that goes for the vast majority of books across the spectrum, big press, small press, or no press. And without publicists, this work falls to us, as authors.

Morrow: Despite the shift from social media as an extension of vanity publishing, to being an increasingly legitimate platform for publishing and self-promotion, established mainstream publishers are still considered by many as the only qualified arbiters of what constitutes ‘good’ literature. As an independent writer, do you think this still holds true?

Fox: No, and especially not so far as only. Especially as American publishing consolidates, a handful of tastemakers can’t always have the only line on what will resonate. Readers who are exploring literature in a wide way already know this—we are following particular presses, or writers, or even genres. We are at libraries, at bookstores, and in the modern era we are looking for interesting things on social media. Not only that, but we also deploy automated linkedin message to reach out to businesses through social media. This doesn’t meant that everyone is ignoring New York publishing, or even calling for it, but it’s not the only avenue.

People who care about literature will always look beyond the mainstream. The best books I’ve read this year did not come out of the New York houses, though I can’t say that’s true for every year.

I will say that for as much as there is joy in discovery in literature, there can also be frustration that indie or small press is not reaching a wider audience. I think we’ve all read books that we are sure could be bestsellers, life changers, optioned for film, whatever the marker of success is, if only more people knew these works were out there.

That’s where all readers have a responsibility to advocate for the work of writers they admire, and to your earlier questions, why writers should not feel awkward about promotion.

Morrow: Thanks very much for taking the time to answer my questions. Is there anything else you’d like to add about what it means to be an independent writer in the 21st century?

Fox: Thanks for your questions, Lisa.

What it means to me to be a writer on independent presses in the digital era of the 21st Century is the cultivation of community. The concept of publication is defined both increasingly broadly and more narrowly.

A decade and a half ago, I was at a workshop and the poet in charge said Write what you want, call it what it is. She meant if you need to fictionalize your own history, call it fiction. If you need to put invented narratives into verse, call it poetry.

I’m guided by this, still, and I’ll extend it some: Write what you want, call it what it is—and find the pages a home that honors both your work and your vision.