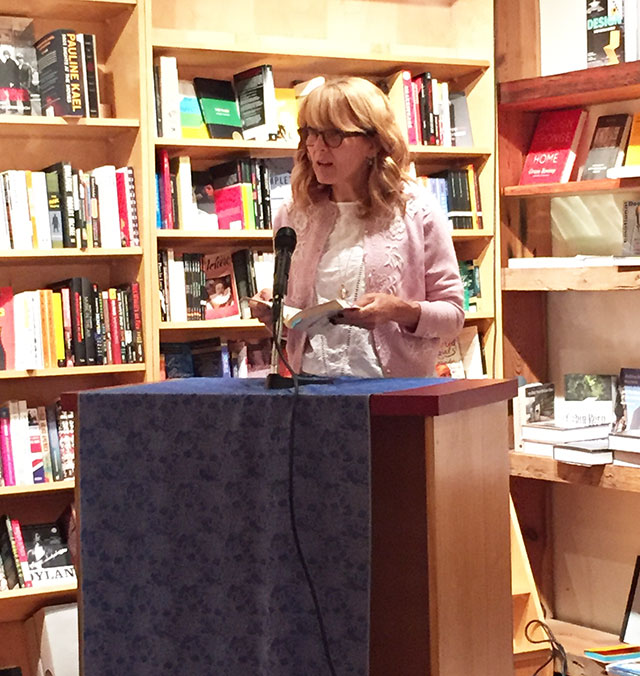

D. Foy launched his latest novel, Patricide at BookCourt and Vol 1 Brooklyn sponsored a discussion with authors Mira Jacob, Will Chancellor, and Elizabeth Crane. Tobias Carroll moderated the group.

The novelists gathered all read from sections of their books confronting parent and child relationships, leading Carroll to ask how they each decided to balance the perspectives.

Chancellor explains that he “fucked” his up. His A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall is about a schism between a father and son after the son loses an eye. He says he thought at first that he was writing about the son before realizing he actually was writing about the father.

Crane intended to focus equally on the mother and daughter, but as the novel picked up momentum, the daughter chapters became harder to write. She tried to imagine what her mother thought the story was. “I had some rough years but they weren’t interesting,” she says.

Carroll asks where they see art coming through in the relationships. For Chancellor, there is a specific idea of the father judging and looking down. There is a sense of moving from outside towards making a mark.

“Artists are never happy people and they never come from happy people,” Foy says. He explains he is always trying to spin his head to solve the world’s problems.

“We create because we are trying to make sense of ourselves.”

“I wasn’t allowed to create as a kid,” Foy continues, explaining that he began making art at eighteen and kept going from there.

Crane is a bit of a different case. Her mother was an opera singer and the was the driving motivation of much of her mother’s life. As a result she didn’t get quite as much attention as a child might like. Her mother told her not be an artist because it was too hard–and a lot of her novel, The History of Great Things–was trying to reconcile being the daughter of this person. She says she doesn’t know if she actually answered any of her questions.

Jacob on the other hand says she comes from a lone line people who don’t have art or passion. Her parents had an arranged marriage, for instance, and she alludes to a family line in the sciences. When her novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing, was released, she was on the way to her book party with her mother and she joked she was ready to become a doctor. Her mother burst out saying she always knew it, not realizing Jacob was joking.

Jacob says she believes that siblings often end up with different versions of their parents based on when they were children and what was happening in their parents lives.

Foy says he didn’t even think of it as a possibility not to have sibling because having them was so normalized. They all have different memories of the same event.

Carroll asks about the importance of setting narratives in a specific time and place.

For Chancellor, he says time and place are inextricably linked. He begins with a time and place, and it is that first image that comes to him when he starts a story.

Foy says he is working on a book narrated by a woman in the 1970s in a nudist colony, meaning place and time are important to the project. He says he worked for a long time to trust himself with the decisions he makes with that narrator.

In the case of Jacob’s book, she set her novel in New Mexico in the 1980s. Nobody knew about it as a place for a long time and then suddenly the Santa Fe Style trend happened.

Carroll observes that the novels have a strong physicality to them.

The importance of that for Chancellor is that he believes it’s an interesting point that fathers and sons don’t share a physical connection in the way a mother would with her children. So he wanted to begin the story with a great physical distance and then have the novel take a trajectory towards proximity.

Foy says he doesn’t believe in the idea of a separation between the mind and the body. He thinks there is really just the body. Everything we do is filtered through that reality. It’s therefore natural for his work to have a lot of physicality to it.