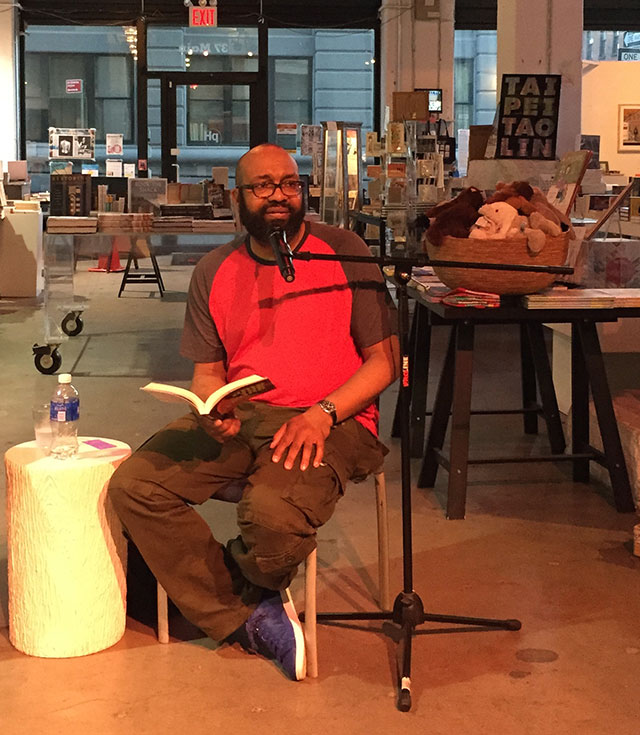

Jabari Asim might have been better known as a journalist and author of essential nonfiction works like his social history the N Word. He has always considered himself a fiction writer though, and now he has released a novel Only the Strong. He spoke about the new book at Powerhouse Arena with Mike Sacks, Asim’s former colleague at the Washington Post and a magazine editor.

Sacks begins by pointing to the immense level of productivity Asim achieves writing and teaching and still managing to produce high quality books.

“I’m not big on sleep,” Asim jokes. Really though his level of productivity comes from pressure he puts on himself. “I have an enormous sense of guilt when I’m not producing,” he explains. Even when he is trying to relax and take a break from writing, he still ends up writing on envelopes or napkins.

While he may not be especially good at relaxing, that quality has some benefits, like the ability to write just about anywhere. “I’ve never needed ideal working conditions.” He says he has always written his books surrounded by his children, working amidst his family. His home office has no door, and he is the father of four, so his family is a persistent presence in his life.

When his sons were younger, he would bring them to poetry readings. They would sit in the back reciting the poetry with him as he read. One of his sons, now an MFA student in New York, was in attendance, although he did not recite his father’s novel.

Fatherhood defines who Asim is as a person and a writer, he says. For instance, he wrote The N Word as a kind of way explaining the world to his sons. he originally wanted seven children. He was one of six, and a large family seemed natural to him. His wife had five and then told him they could have seven if he had the last two.

Asim always thought of himself as a fiction writer, and though he has published more nonfiction, the fiction was always present. He would write nonfiction in the morning and fiction in the afternoon. Eventually he sold the story collection A Taste of Honey. He sees that collection as a predecessor to the novel. The collection and novel each focus on similar characters in different decades, and his next fiction project would ideally move ahead in time yet again.

Asim left college before finishing his degree. He holds none. He took a job in St. Louis working at a Sears selling televisions. There were more print publications when he was starting out, so he would talk to editors and try and sell them on stories. “I needed a victory,” he explains. He finally sold his first news story for thirty-five dollars.

In the time he did spend at college, Gwendolyn Brooks taught a short three-day residency. She came as part of the Women’s Studies program. Asim says he was the only guy in all of the classes. He was a bookworm. He also says Brooks’s residency transformed him in a significant way. Mostly he realized he didn’t want to be a lawyer.

When he was growing up, Asim was part of a gift student program and was sent to a school that was predominantly white. He played on the tennis team and he remembers his tennis coach becoming very concerned about her purse whenever they played a predominantly black school. It was especially awkward for Asim since his father coached the tennis team at a rival, predominantly black school.

St. Louis is a big part of Asim’s writing and of his life. He says he doesn’t recognize Jonathan Franzen’s version of St. Louis in the novel The Twenty-seventh City. He also adds that lots of black St. Louis citizens have links to Mississippi. Both sets of his grandparents originally came from Mississippi, for instance. His grandfather ended up working as a gangster in St. Louis running numbers.

When he was starting to write books, he explains that his agents didn’t want fiction from him, they wanted nonfiction. He would prefer to stick to writing fiction. “I never set out to write any nonfiction books,” he says.

Asim wrote the ending of the novel early on. He knew where he wanted to go, and he knew he had to get the characters all in one place. From there, things fell into place logically.

Some characters are easier to control, Asim explains. “When you are planning the fiction, you have certain ideas for characters.” Sometimes they obey and sometimes they don’t. “I try not to make it too mystical,” he adds.

“I’ve probably read every page aloud before releasing it,” he says.

He is working on a new book. He says he wants to write a slave narrative at some point partly as a response to criticism that black authors are spending too much time with those narratives. He disagrees.

As far as film adaptations, Asim isn’t holding his breath: “I don’t think Hollywood knows these books exist.”