Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. has been favorably compared to Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City (1985) as a portrayal of the contemporary New York City literary scene. McInerney himself drew the comparison when he sat down with Waldman in Barnes & Noble. Waldman, like the literary scene itself, focuses her story in Brooklyn. Though intentionally obscured, the novel unfolds unmistakingly in Fort Greene and Crown Heights. Amidst the rapid gentrification, Nathaniel (Nate) finds himself dating fellow freelance writer Hannah. Over the course of the novel, Nate’s inaction and apathy leads to the eventual unraveling of their relationship. At the most fundamental level, Nathaniel P. is the story of two people gradually allowing distance to taint their relationship.

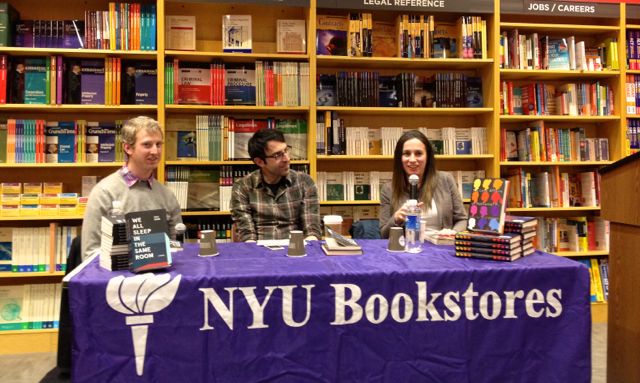

Much is the same premise with Paul Rome’s We All Live In The Same Room. Narrator Tom lives with Raina and their son, Ben, in, as the title suggests, a one bedroom apartment. Its rent controlled, of course. Despite sharing the small space, like the characters of Waldman’s novel, Tom and Raina spend the duration of the story drifting ever farther away from each other. Though Tom and Raina are more proactive about hurting each other than Nate and Hannah, ultimately they are all victims of unforeseen emotional distance. Given the similarities, the two authors form an ideal pairing, and NYU Bookstore brought them together for a discussion moderated by Paul Morris of Pen America.

Rome read first, choosing the one section of the novel that portrays narrator Tom in a positive light: his interaction with his son Ben. Much of the novel vilifies Tom. He’s an unlikeable character who primarily is redeemed only by the kindness he expresses with his son.

Before reading, Waldman explains that her first introduction to Rome came over twitter–he had been tweeting about reading Nathaniel P. She read from the second chapter of the novel, a section of backstory that looks at Nate’s life during his high school years before he’s achieved the kind of aloofness and savvy cool that allows him to neglect the people with indifference.

When they finish reading, Paul Morris begins the discussion by asking what it was like for each of them to enter in the minds of characters so different from themselves.

“I was channeling certain anxieties of getting older,” Rome says. He started writing the novel at the age of twenty-five, and narrator Tom is forty-six. It was a kind of way to imagine his older self, or a version of his older self. He wanted to explore what is like to an older adult having life unravel. He was working as a babysitter at the time, too, placing him in a position of observer of people further along in their lives.

Waldman took a slightly different approach. She wanted to inhabit a certain kind of guy and capture the essence of the things that frustrate women. But fundamentally, it was about understanding a life that wasn’t hers. Still, she admits a lot of her remains in Nate: suburban, middle-class origins, the culture shock of college. Though Waldman draws on the literary scene as a kind of anchor for her characters, she wanted Nate to have relatable traits even for people outside of that world. She simply wrote about writers in Brooklyn to simplify the writing process: it was something she already knew about.

By contrast, Rome’s protagonist, Tom, works as a labor lawyer. One subplot involves Tom’s defense of a unionized health care professional. For the legal procedures, Rome turned to his father, a labor lawyer, and his Uncle, who works at a firm in midtown. Rome also spent a summer as an intern making photocopies there, he explains. Whenever his characters faced legal issues, he would write a paragraph and shoot it off to his father to look over for verisimilitude.

Rome asks Waldman about her perception of the typical male, since Nate comes across as somewhat sensitive, and even perhaps a bit feminized, particularly in the passage she read.

Though Nate is meant to have widely recognized characteristics of typical male behavior, she also didn’t want him to be an alpha male. Rather she wanted to portray an image of a nice guy–who happens to be flawed in common ways. Waldman seems to struggle with describing Nate’s offenses, and that subtlety is where the magic in her characters exists. Nate never does anything horrific. Nate has his reasons, she says, although he isn’t a monster.

“No one has unequivocally liked my character,” Rome says. Though he adds that over many drafts, Tom evolved. “He wasn’t a monster to me but he was reading that way to others.”

There is a disconnect between the reader and the author, Waldman says. Authors have access to information about the characters and backstory that the reader never does and sometimes authors forget about this privilege.

Morris asks both authors about the women in their books. Both novels shunt women into supporting roles, but these characters also turn out strong and dynamic.

Waldman suggests some of her women are as unlikeable as Nate. “In moments in writing this book I felt like I was throwing women under the bus,” she says, “to make it feel real to men, the women had to feel flawed.”

The early drafts of Rome’s book featured women who were far too attractive. “That’s how I pictured them!” he says. He eventually had to write them as less attractive people. In his case though, any of the secondary characters were filtered through his first person narrator.

And as the author, Waldman notes, there is so much information about the characters, it becomes difficult to naturally add it in.

Rome points to an interview with Rachel Kushner where she discusses the limits of character point of view. He also adds that while novels seem to trend toward offering every character their own chapter, he prefers to have a singular perspective.

“I didn’t want to make characters any simpler than people I knew in real life,” Waldman says. “The characters just had to feel real.”

Rome started his novel in 2005, spent two years writing a draft and then took a break. He then spent as much time editing. He also says that one point the now thin novel ballooned to five hundred pages. He mentions Zadie Smith’s interest in Lyrical Realism, but says that was a false path for him.

For Waldman, editing is simply the process of getting to the book that the author has been writing all along. Nathaniel P. took five years from genesis to publication. But in that time, even though its the exact same plot as she began with, its an entirely different story.

“There is a moment you realized you’re writing for an audience,” Waldman says.

During his two year hiatus from working on the novel, Rome explored literature as performance. He also learned to cut the cheap jokes. For much of that time, he has worked at a Bushwick cafe. He says that caffeine is good for writing, and it got him up early. “To save those afternoons for yourself is tough,” he says.

“I feel lucky to live in a neighborhood where being a barista isn’t looked down on,” he adds.

Both novels look at how New Yorker’s live. Its simply not a New York novel without at least some discussion of real estate.

For Waldman, she saw her characters’ relationship with gentrification and the Brooklyn neighborhoods they inhabit as unavoidable. Class is an important part of who they are.

For Rome, his characters live in a one bedroom apartment because he knew a family that actually lived that way, and he wanted to explore the idea of sharing space with people. He wanted to think about their sex lives. Also, Tom, a labor lawyer, hasn’t given up his blue collar roots and the rent stabilized apartment is something of badge of honor.