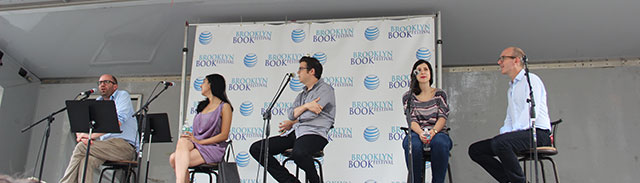

The London Review of Books hosted a panel on 21st Century Narrators at the Brooklyn Book Festival. LRB senior editor Christian Lorentzen moderated Elif Batuman, Ben Lerner, Christine Smallwood, and Lorin Stein in a discussion. Batuman is a non-fiction writer who regularly contributes to The New Yorker and author of The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them. Lerner is the author of the novels Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04. Christine Smallwood is a columnist for Harper’s Magazine and Lorin Stein is the editor of Paris Review.

Narrators earn reader sympathy by being victimized, Lorentzen begins the panel by explaining. The night before the book festival, he continued, he was robbed. His bag containing his laptop, his favorite corduroys, and many books was stolen. The thieves left behind most of the books, but it being Williamsburg, he conjectures they took two novels by Ben Lerner.

Recently appearing in the London Review of Books was Lerner’s review of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s latest volume, a translation of his memoir. As a narrator, Knausgaard fails to distinguish between the values of varying experiences and objects. Both minor and major events are treated similarly. Lerner claims this choice drives the narrative. Everything in the novel enjoys equal intensity whether its a major or minor event, and the drama is, according to Lerner, in learning whether Knausgaard is capable of making those distinctions.

Lorentzen turns to Batuman and asks her about her views on MFA programs. She previously reviewed The Programme Era in the LRB.

Many of her views have changed, Batuman explains, because many of the authors she now admires are employed by MFA programs. Her criticisms though of the ideas behind MFA programs still hold up. First, the idea of finding your own voice, and second, writing what you know. She says these two ideas evolved from the cold war era programs, with the idea of entering the ether and emerging with new ideas. She believes in a more contemporary ideal. There is honesty in living experiences–describing an experience in itself is new because no other person can experience something in the same way, even if it is something that has been experienced before.

Lorentzen turns to Lorin Stein, editor of The Paris Review, and asks about the rise of Know-Nothing Narrator. Stein explains that it derives from the preoccupation with the boundary between art and life.

Smallwood explains that part of that difference is the distinction between reproducing reality and accessing a world that is similar to reality but distilled. Sheila Heti is interested in reproducing reality, word for word. An author like Akhil Sharma, especially in his most recent novel, Family Life, is more interested in reproducing a refined version of reality. It draws on real life, nearly autobiographical in nature, but perfects the narrative. Instead of focusing on a direct reproduction, the narrative cherry-picks the best moments to construct an ideal narrative.

“I’m interested in the way fictions become fact,” Lerner says. Real experiences are transposed into fiction and then bleed back into life, he explains.

Batuman’s first book, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, is a non-fiction exploration of her time studying Russian novels, but she is currently working on a novel of her own. Lorentzen asks her to explain how this transition feels from the standpoint of crafting a narrative.

Non-fiction is automatically more compelling, Batuman says. Fiction requires more than a quirk or hint of humor to carry a narrative. Readers accept more flaws in non-fiction because its something that actually happened. The other major concern with fiction is that everything is part of an invented world. Readers enter with less knowledge. With non-fiction, dropping a historical figure gives readers some immediate information, but in a fictional world, everything is unknown until the narrator illuminates it. A historical figure in a fiction may not have all the qualities of the historical figure in the real world.

On the other hand, moving towards fiction means eliminating any kinds of privacy concerns. Even characters based on real people end up being merely reflections. Privacy, ultimately though, is something primarily that men have imposed on women.

Stein offers that there is a distinction to be made between between The Real and reality. One is torn from life, one a reflection of it. Often the reception of one or the other determines how invasive it feels.

“Reception is totally gendered,” Lerner declares. Often how a work is received depends on whether the author is a man or a woman. Women often find they face more criticism, and different cricisims.

Fiction and reality also have different narrative timelines. Fiction can compress time and space while non-fiction is limited by actual events.

“The novel arises as this problem in time,” Lerner says. Its a way for experiencing the condensation of time. He criticizes contemporary novels–bad contemporary novels–as imitating the works of the 19th century. He says that bad 20th and 21st century novels come from 20th century television that have had their plots run through the conventions of 19th century novels.

The know-nothing narrator resides in a small subset of the American and European fiction, Stein says. As an editor of a journal with a large slushpile, he can see trends in writing. The tastes of the average submitter change over time. For a long time, there was interest in the pastoral fiction where main characters are simple, though written for sophisticated readers. This form tends to be dominant.

“If the novel comes out of TV, its because we all grew up watching TV,” Stein says.

Not all television is bad though, Lerner assures the audience. He describes enjoying The Wire because its Dickensonian. He is quickly corrected by Smallwood who says its more Zola-esque. Either way, Lerner says that television unadulterated with advertisements creates interesting narratives. “I think capitalism is bad,” he says.

Batuman says that artists can’t escape capitalism.

Nevertheless, the impact of television on narrative is hard to ignore. Lerner criticizes many novelists who he claims are trying to get readers to forget they are reading a novel.

Historical fiction is growing in popularity in Britain. Stein says that in the slush pile, there aren’t many historical short stories. Partly its difficult to access the characteristics of a historical novel in a short piece.

Batuman says though that historical novels offer some advantages. Its easier to capture the spirit of the times simply by not being in the times and looking back. Being removed from a particular time allows better perspective. It also eliminates the problem of privacy. However, there is always going to be a clash between historical characters and imaginary ones.

Christian Lorentzen, Elif Batuman, Ben Lerner, Christine Smallwood, and Lorin Stein

Sunday, September 21, 2014

Brooklyn Book Festival