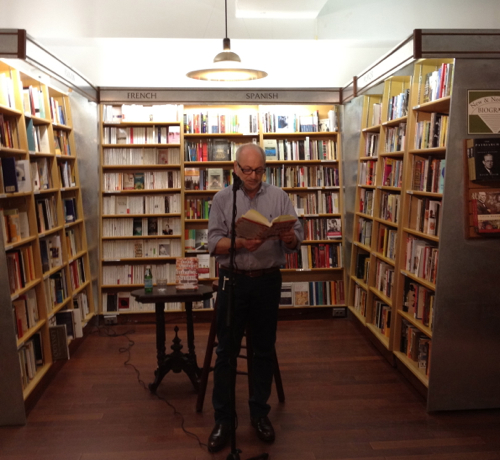

“Memoirists, unable to erase the ugliest moments of their past or unwilling to make new ones up, can shift them around” André Aciman wrote in the New York Times last week. Storytelling is not about a genre of memoir or novel, Aciman is suggesting, but in the truths held together by fictive narratives. Such is the case with his new novel, Harvard Square, borderline memoir, inspired by a character he knew in graduate school, but written through a fictional lens. Aciman has been reading around town to promote the book; on Wednesday he read at McNally Jackson Books.

Aciman simply begins speaking as though carrying on a casual conversation with the audience, telling a story about this one time in graduate school — and then he opens the book and reads. The first person narrator exists as some facsimile of Aciman, and the backstory he provided the audience also sets up the novel excerpt.

The narrator, having flunked his oral exams, is spending the summer reading in the Cafe Algiers, a real Harvard Square coffee house that Aciman spent a summer reading in after having flunked his oral exams. The audience is introduced to Kalaj, a mysterious seducer of women, a cigarette smoker, an adventurer. Aciman stops reading and begins to fill in more backstory as though telling us about his life once more before flipping through his book and picking up again. He transitions effortlessly from text to conversation back to text.

The prose is concerned with repetitions, patterns in the words that reappear. Aciman offers lists of objects, some to inject humor, some to capture a sense of place, others to achieve the necessary cadence. Rhythm is important to his sentence structure, and each has been written with care. The narrator continues on by analyzing his behavior, his choices, his actions, his inactions with a deep introspection.

Aciman floats between narrator and author reading from a half dozen segments interspersed with seemingly off the cuff tidbits propelling the narrative forward. When he finishes, the audience is left with a well rounded sketch of Kalaj, the man who seduces women with self-rolled cigarettes.

Aciman opens up for questions and an audience member asks when he wrote the book: a long while back, he says. The novel began as a story for The Moth. Aciman had been asked to speak about a “memorable person” and chose Kalaj, someone he knew from years before. He made notes. He reviewed the story and found it boring as it had been written. He put it aside and wrote other books. Later, he picked up his notes again, rewrote it as a short novel; it was published by the Paris Review, first as a short story, winnowed down by an aggressive editor.

Eventually Aciman went back to revisit the narrative and converted into the novel. All this for a character he described as “so unimportant I wouldn’t have written about him in a diary.”

Aciman explains his interest in finding distance and a sense of loss about his subjects before writing about them; the decades between his time in Harvard Square and writing of the novel allowed him the perspective to capture Kalaj. This distance is essential, he explains, like with travel writing — he returns home before writing about the place in order to create that space.

The importance of that distance allows for the connections necessary to create a narrative and allows for linking those otherwise unconnected moments into a plot. Real life has no plot, no centralized narrative: “all memoirs are really novels because you are telling a story,” he says. By connecting events that are otherwise unconnected, a writer crafts the narrative. The reason distance is so important is that once a memory is written down, that memory becomes contaminated with the written form. The original scene disappears.

Harvard Square is now available in hardcover.