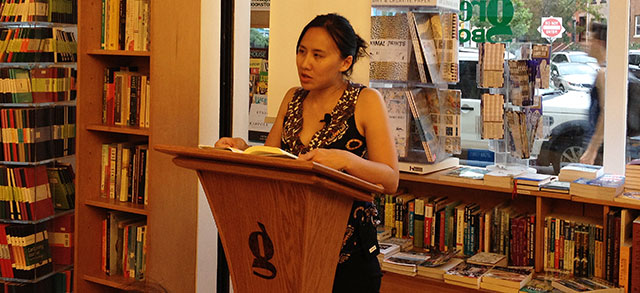

The Asian American Writers Workshop hosted Celeste Ng at Greenlight Bookstore to discuss her debut novel, Everything I Never Told You. She was joined by Catherine Chung, author of Forgotten Country (2012).

The Lee family has three daughters, one of them dead, though as the narrator explains in the opening line of the novel, nobody knows that yet. Everything I Never Told You tells the story of an interracial couple in 1970s Ohio raising three daughters, one of whom disappears and dies. The novels title alludes to the secrets of the family.

Ng says the idea for the novel sprouted from a story her husband told her. As a child, her husband’s sister was pushed into a lake by a classmate. His sister survived. But for Ng, the fear of drowning in a lake stuck with her, partly because she herself is a terrible swimmer. She began writing with the idea that Lydia would die, and the remaining family members grew from that point on.

Both Ng’s parents work in the sciences. Her father was literally a rocket scientist for NASA and her mother a chemist. “I am kind of a science nerd,” she says as a result of STEM-centric family. But she was also the youngest: “I was always the one off reading fairy tales in the corner.”

She says that despite the common belief that art and science are diametrically opposed fields, she sees them as very similar. Both are seeking to find anomalies and explore their meaning, and both are interested in cause and effect. As with science, the best fiction looks at a small portion of the world and tries to make sense of it.

The most difficult scene to write was the moment Lydia’s parents read her autopsy report. Ng explains that she recalled receiving the autopsy report of her father. She kept the sealed report for a long time. Eventually she read it, finding it a painful experience. Writing the scene brought back the same uneasiness she felt while reading through her father’s report.

The novel is set in the 1970s. When she first started writing it, a creative writing professor suggested she simply set the novel during the 1990s, when she grew up. The advantage would have been avoiding the complications of researching historical accuracy. She tried altering the year in one draft of the novel, but found issues like gender bias in medicine, for instance, felt anachronistic in the later period.

Nevertheless, many of the events in the book are based on real incidents. As a chemist, her mother faced regular, if subtle gender bias in the workplace. She would often be the only woman and her coworkers often questioned her ability to balance her performance both as a chemist and mother to her children.

Most of the incidents of racism in the book were things that happened to Ng or her friends. “I didn’t have to make a lot up,” she says. One intentional choice she made was in language. The term Oriental sounds outdated today, by then it was both normal. To modern readers, it seems particularly abhorrent.

“I remember one day it was gone,” Catherine Chung interjects, referring to the term. Chung says that during her childhood in the 1980s it was acceptable and then it seemed that overnight it was replaced by the phrase Asian American.

Ng never expected to write a novel about Chinese Americans or even a mixed race couple. “I know a lot more about typical white suburban America,” she says, adding that maybe deep down she really did want to. She says her mother was always trying to get her to read immigrant narrative books, and found that they featured two kinds of immigrants: hard working immigrants who succeed and immigrants beaten down by racism.

Race and racism, though, is more subtle than that. For instance, from her own experience, she says people say to her they are surprised she has no accent or they ask where she is from, repeating the question when she tells them she grew up in Cleveland.

The novel is a book with Asian characters, but it doesn’t need to be. “For me, its really a family story,” she says. The parents in Everything I Never Told You are an interracial couple. Though Ng’s husband is white, writing about interracial relationships sprung organically from the writing process. It was not her intention to necessarily tackle issues of interracial couples, only that the characters seemed to fit in the story she wanted to tell.

“If you can only write about yourself, you have a very limited view of the world,” Ng warns. But she also adds to that, “you have to be as authentic as you can.”

Ng would in the past often allow herself to an undisciplined approach to writing. She spent six years writing four drafts of the novel. Halfway through she had a son. Now she says she must adhere to a specific schedule. Whenever her son is in preschool, she sets to writing. She usually has a snack with her, sometimes Swedish Fish, sometimes hot Earl Gray tea. Still, throughout the day, even when she isn’t writing, she will leave herself notes to return to.

Last week, Ng wrote a piece in for the New York Times Magazine about her mother’s cookbook. The quaint 1960s cookbook included many gender biased phrases about baking pies in order to please a man. She says she included these anecdotes borrowing directly from the real world for her novel. She offers one more bit of advice: “If you’re going to write a piece about your mother, be prepared when she talks to the fact checker — its going to an awkward conversation.”

Celeste Ng and Catherine Chung

Wednesday, July 10, 2014

Greenlight Bookstore