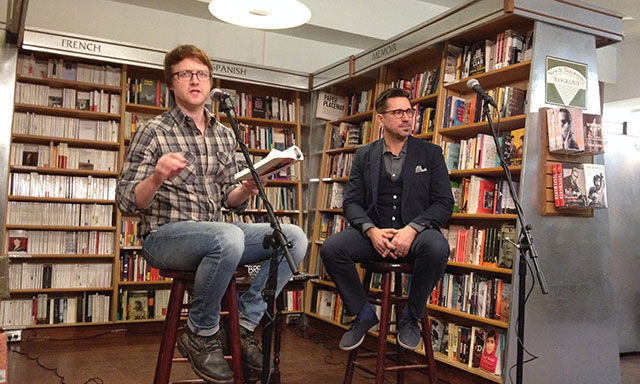

D. Foy’s debut novel, Made to Break was sixteen years in the making. It is the story of five friends trapped in a mountain cabin as they explore their various failures and vicious behavior. He read from the novel at McNally Jackson and was joined in conversation by Sean Madigan Hoen. Soho Press will release Hoen’s memoir, Songs Only You Know next month. It examines his crumbling family alongside his time as an indie musician.

Made to Break unfolds over thirty-six hours in a remote cabin. A group of friends, coming down off a drug bender, plan on taking it easy over the New Year with just a bottle of bourbon. A storm traps them on the mountain. But they have forgotten ice for their drinks, sending two of the group out to find some. Ultimately, they are forced to confront the terrible ways they behave and the viciousness of their lives.

Hoen prefaces the discussion by stating that he and Foy have known each other personally before ever meeting as writers. He seems worried their relationship will taint his interrogation. Hoen proceeds by citing a review of Foy’s novel: “Overall, Made to Break is an entertaining, at times artful piece of pulp trash (and I mean pulp trash in the most complimentary way) that will leave the reader spinning.” Pulp trash describes Foy’s concept of “Gutter Opera,” a merging of the high and low, and Hoen asks him to elaborate on the concept.

“My mother tongue is trash,” he explains. Foy says he came to art from the streets, adding that that one day he decided to write a poem–without ever having read any poetry. His first attempts were not very good, though he felt more excited after writing out a story. But he also knew he lacked the necessary background–from an educational standpoint–to participate in a meaningful narrative.

School was for him a way of discovering new influences. “I really wanted to know what I wanted to know,” he explained later in the evening. He says he would be assigned a book, and then end up reading ten more to better understand it. He’s also critical of writers who become professional writers by going from college to graduate school without having any real world experience.

He was older before he attended college. He says he put himself through school because he wanted to learn. Education for him was about taming the experiences he had accumulated in order to funnel them in a productive way. But in school he learned a new lexicon, one that he says felt rarefied.

At first he wanted to try and emulate the authors he read in school. He was particularly fond of Faulkner. He wanted to write in a “normal” style. But copying other writers’ aesthetics didn’t work.

Gutter Opera, as he names it, is the merging of the profane and vulgar with these other loftier ideals. “Its more or less the way I think,” he says.

The characters of the novel respond improperly to their situations, Hoen says. They are highly controlled characters, but in scenes that require empathy, they often respond in the opposite direction. Hoen describes much of Foy’s novel as David Lynchian with dramatic moments exploding reality.

Foy picks up a copy of the novel and turns to one of the black printed pages in it. He says the black pages are intended to function in the same way as a cinematic fade to black. He feels heavily influenced by film, especially by David Lynch. As an artist, Foy says, he there are many things that he consumes and doesn’t think about, but then draw on them as he needs them.

In writing his book, Hoen says, he ultimately omitted many true things that interfered with the understanding of the truth of the story. He assumes with Foy’s characters, many of them are composites of real people and asks about how they were created.

Foy says he ran with a group of people at least as vicious as his characters. “I didn’t know how not to do it,” he says. He did eventually distance himself from those people. What interested him though was in what held those relationships together.

“The important thing is, I put part of myself in all of them,” Foy says of his characters. He wanted them to feel human.

For a time, Foy says he didn’t believe in goodness. Life felt like a never ending pounding of a malignant hammer. But now he feels he has an inherent faith in people and believes in their goodness. Ultimately he wanted to break his characters down into their human essence.

Since the novel is set in 1996, Hoen says, he wants to know how the zeitgeist sense of nihilism affected the characters, especially in contrast to the idea of irony.

Foy points to an interview he gave to Scott Cheshire in Tottenville Review where he mentions irony. He says there:

“The story begins on the day before New Year’s Eve 1996, an era, I’d say, just before we were crushed by the epidemic of irony that in my opinion has us still in its grip. Or rather, I should say it was an epidemic that’s mutated and morphed and finally become something of an insufferable condition. Irony today suffuses everything we think, say, and do. There’s nothing that’s not ironic anymore, not even ourselves—irony is our way. Our irony is a white sheet of paper.”

The 1960s, Foy says was full of idealism. The 1970s was an exaggeration of that period, setting up the era of abominations under Reagan. Irony then wasn’t a weapon as it is now. These characters see irony used as a mobius strip.

Made to Break first came into existence in 1998. Foy spent years reworking the structure of the novel. He also moved onto other projects. By the time the novel sold, he felt distant from it. He worried as the book moved forward that he would not be able to get behind it. He had changed over the course of sixteen years since first writing. But then he had a revelation: employing the metaphor that an author’s books are his children, Foy says he began to realize this novel was the runaway who had finally come home. The book had been abused, beaten, scarred, and now that it had returned, he, as author, had to embrace it.

The first draft was close to four hundred page. Over the years he cut it down to two hundred. Whenever he felt despaired, he would dust off the book and manipulate it slightly before putting it aside again. Only in the final year before publication did he begin manipulating the language again. When he started working closely with the text again, he says he was able to embrace it.

Foy then turns to Hoen to ask about his forthcoming memoir. He says the book transcends traditional rock and roll memoirs in that it seamlessly integrates the tragedy of family life alongside the musical career.

“I was insecure with the band aspect of it,” Hoen says. Music memoirs have different aspirations than literary books, he adds. He wanted to avoid mentioning the band by name, but eventually realized he couldn’t totally leave it out. The manuscript felt too elusive without proper nouns.

Hoen seems to still be growing accustomed to turning the narrative on himself. “Its a little more than I bargained for,” he adds. “I kind of did in a bubble without really thinking of it,” he said.

Songs Only You Know will be released next month. Made to Break is available now.

D. Foy and Sean Madigan Hoen

McNally Jackson Boooks

Tuesday, March 18th, 2014