If there is a literary equivalent of a shock-jock radio D.J., it might be Emily Gould, the essayist, memoirist, and blogger known for honest confessionalism, sometimes criticized as bordering on narcissism. Her 2010 collection of personal essays And the Heart Says Whatever earned her a $200,000 advance, and then the book flopped, as she describes in the essay “How Much my Novel Cost Me.” Gould now returns with a new book, the novel Friendship, but the distinction between fictional and nonfictional narrative remains insignificant. Gould pulls inspiration from her own life and that of her close friends creating a story of the friendship of two young women as they bumble through their twenties in New York City. Comparisons have been drawn to Lena Dunham’s Girls, though perhaps without the glitz and glitter of an HBO set. While Dunham’s girls’ blunders transpire across the Disneyland like paradise of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, a romanticized version of an already saccharine sweet world, Gould’s young women, Amy and Bev, find themselves in the distinctly less glamorous if equally expensive brownstone neighborhoods of Brooklyn.

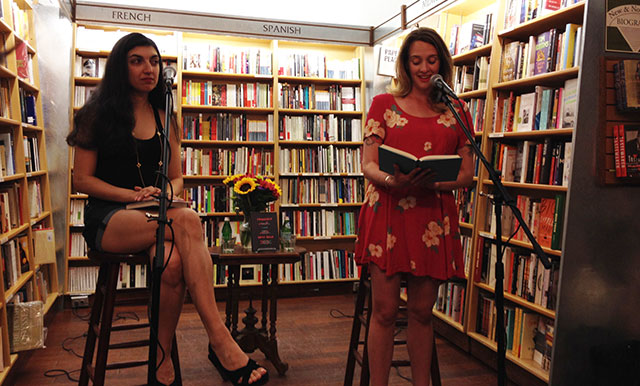

McNally Jackson books hosted Gould to celebrate the launch of Friendship. She was joined by Elif Batuman, author of The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, a collection of essays.

In 2011, Gould and Jon-Jon Goulian faced off at a Literary Death Match. Goulian won, but in the audience was Gould’s editor, Miranda Popkey. Based on the performance, Popkey decided to go after the manuscript. Gould reads the same selection, now heavily edited. She is a natural performer adding inflection and intonation and bringing to life the two characters. The scene is a flashback. Amy and Bev are living in New York City, but Bev prepares to move to Madison, to be with a boyfriend in law school. Bev imagines herself marrying the law student, though he is having an affair. When a car accident kills the other girl, Bev discovers the affair. Its a moment of sincerely ambiguous emotion as Bev breaks up with the law student to return to the city and Amy.

Batuman begins the discussion by asking Gould about the transition from to the third person point of view. As an essayist and blogger, Gould built a career writing wrting from a first person perspective.

“I started writing in third person as an exercise,” Gould says, adding that she found that she had exhausted the first person voice. It was becoming impossible to write in the first person. She says she hopes to regain the ability to write in way that is “stupidly fearless” again, but as she has gotten older, the consequences of writing about herself have only increased.

The novel nevertheless retains Gould’s memoirist tendencies. Amy is based on Gould, and Bev, on her friend, though perhaps really, they are both just different versions of Gould. Amy, as Gould explains, looks like Emily Gould, but its Bev who endured the emotional trials. She says she ultimately felt closer to Bev, and by the final round of editing, stopped understanding Amy. She thinks its maybe a sign that she is maturing. Amy became a challenge for Gould to find enough compassion to be kind toward her. Often Gould was punishing her too much.

“Amy is the person you imagine I’d be if you never met me,” she says.

Batuman asks about the success of the two characters in the novel who are visual artists. Sam, Amy’s boyfriend, sells paintings of countertop appliances and Jason is an interior designer. Both are financially sound, the opposite position of Amy and Bev who teeter on the brink of insolvency throughout the novel.

Gould explains that she thinks visual artists have a better baseline of what is expected from their work. They can more easily find success, if not financially, because its much more explicitly defined. For writers, the expectations and definitions of success are much less clear. There is less money in writing. The idea of being successful enough to survive from writing alone is the same kind of fantasy of becoming a successful Hollywood star; its unrealistic.

She also sees a distinction too in that Amy and Bev are both children of typical middle-class America, children of boomer parents. Sam on the other hand is an immigrant. His expectations are different and more frugal, and he seems better prepared in the world. Gould says the most poisonous thing she has ever been told was to do what she wanted and the money will follow.

Batuman asks her if she has read Kar Ove Knausgaard’s epic multipart memoir, drawing a comparison to the fervent honesty of those books to Gould’s novel. Gould hasn’t read Knausgaard, and says its been a long time since she has read a first person, white, heteronormative male novel. Gould primarily reads female authors. Partly this is in the hope of finding new selections for her subscription based bookstore, EmilyBooks. EmilyBooks is also getting ready to begin publishing new books. Primarily though, Gould says her disinterest in male authors is reactionary to the traditional western education regime that favors white male authors. Its not a hard rule though, she adds, confessing to having read the Game of Thrones books.

In the essay “How Much my Novel Cost Me,” Gould sets up a paradigm of two kinds of ways authors lead their lives, at least in fantasy. First, the author as celebrity where a published book makes the author an authority on many different aspects of modern life, and second, the novelist who lives successfully pays for a bourgeois life in Brownstone Brooklyn with book royalties. “I don’t think think either of those things exist,” she says, saying writers ultimately need to get full time jobs. “You can work. You can save money. You can not care about bullshit things.”

Money is a major recurring problem facing Bev and Amy. They meet in publishing, and later struggle to find out how to pay their bills with Bev working as a temp and Amy quitting her job as an internet writer. Money serves as a way to bring Bev and Amy together as well as driving a wedge between them.

Friendship is also though a novel about a relationship between two women. “They’re intimate in a way that has nothing to do with sex,” Gould says. Its a monogamous pair bond with the sex. Gould says that often women in film and literature talk to each other only ways that relate to romance with men, and their conversations are a foil for those romances. Its an echo of the Blechdel test. “In monogamous relationships you can fix a lot of problems by having sex,” Gould says. The same is not true with Bev and Amy.

Gould is also a lightening rod for criticism. She sees a few reasons for it. “I’m really honest and don’t apologize for being forthright about things,” she explains. But a lot of the vitriolic criticism is personal. She sees this as a broader problem saying that for many people, the internet is a frightening place. They don’t necessarily know how the internet functions and it scares them.

She also believes a lot of criticism comes from artistically frustrated middle-age men. She sees herself as empowering young female voices. “I’m sorry if that fucks with your world, dude,” she says. “There are some people, especially men, who never read books by women,” she says. It never occurs to them that they are missing out on other perspectives.

Gould said she expected a lof of the criticism to be better this time around because she was writing a novel rather than personal essay collection. Instead, much of what was written about her focuses on her time in 2008 as a blogger. She jokes that she’ll probably have to write another four books before people let go of that piece of biography.

Emily Gould and Elif Batuman

Thursday, July 10, 2014

McNally Jackson Books