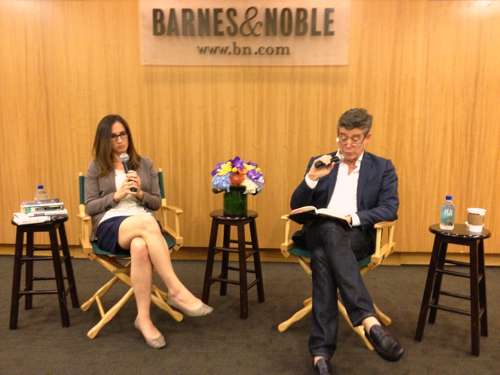

Adelle Waldman’s debut novel, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. has become something of a sensation since its July launch. Waldman was joined by Jay McInerney at the 86th Street Barnes and Noble.

McInerney began the evening by reading from Waldman’s book, the quote, the obvious choice:

“’Men and women on relationships are like men and women on orgasms, except in reverse,’ Jason continued boisterously. ‘Women crave relationships the way way men crave orgasm. Their whole being bends to its imperative. Men, in contrast, want relationships the way women want orgasm: sometimes, under the right circumstances.'” (214)

Nathaniel P., at its heart, is a book of relationships. Nate, the ostensible protagonist, weaves in and out of several, while Hannah, the object of his affection, deals with his uncertainties. Nate is a character everyone can hate and relate to, either as a man sharing his experiences, or a woman, enduring his ambivalence.

At times the book feels like Hannah’s narrative, but the perspective belongs to Nate alone. The question of this choice is a common refrain with Waldman seemingly drained from the question. She is practiced in her response. She knew she wanted to write a novel about relationships and for a time thought of the narrative from the perspective of a woman. But she was drawing upon the collective experiences of her friends and herself as twenty-something women. Only then did it become apparent that she needed to address the story from a man’s perspective to achieve the sort of insight and analysis in Nathaniel P. And she achieves it brilliantly.

Waldman says of herself that she must be “deeply cynical” because she saw herself as writing a realistic portrayal of Nate–flawed, but not terrible. And yet, most of the response has been how horrific a person Nate comes across as. Yet, Nathaniel never does anything terrible in his behavior. He doesn’t have affairs, for instance. His betrayals are never in actions, but instead through his thoughts.

The narrative comes from Waldman considering a typical relationship trajectory. She always envisioned the end of the novel as a natural conclusion to the relationship, and wrote towards that and with that ending in mind.

Writing the novel was about finding moments that were unlike how she would experience the world. “I focused on the parts of Nate that are different from me,” she says. Though certainly there are similarities between herself and Nate, despite the gender dichotomy.

Still, she hesitated asking male friends about the characterization. She wanted to avoid interview like questions knowing they could never answer honestly, even if they intended to. It would be impossible for men to accomplish the kind analysis the narrative voice is able to unearth.

A big component of the book centers around Brooklyn and the literary scene. Here, and throughout the discussion, both Waldman and McInerney draw comparisons to McInerney’s 1984 novel, Bright Lights, Big City. McInerney’s novel captures a scene of writers in 1980s Manhattan, in clubs, doing drugs, living the writerly life of the moment. Waldman inadvertently has accomplished the same feat. She wrote about writers in Brooklyn because that is who she and her friends were, a world she knew.

[pullquote]”It got lonely; all my friends lived in Brooklyn.”[/pullquote]

McInerney suggests too that Waldman’s novel has captured a cultural shift, the rise of Brooklyn as the center of the New York writing scene. When he first came to New York, that cultural center was squarely in Manhattan. Largely, then, it was centered around George Plimpton of The Paris Review; Plimpton’s 2003 death marked the exodus to Brooklyn, whether by coincidence or not is unclear.

And perhaps there is something to this. Waldman first moved to Manhattan in 1998, but then “it got lonely; all my friends lived in Brooklyn.” She since followed her friends, writers, outward.

Brooklyn plays a distinct performance in the novel. Although Waldman cloaks her neighborhoods and avoids naming them outright, the similarities to Fort Greene and Prospect / Crown Heights is evident. The richness of the environment helps to attenuate the overbearing critique of gender, and rightfully so: “If it were just about gender it would be very flat,” she explains.

Waldman also doesn’t simply play with gender, but also a broader, modern multiculturalism. Race, ethnicity and religion in the novel offer a range of diversity. Hannah, a Catholic, even jokes about Nate’s judaism. Waldman explains that in her parents’ generation, these quips would have been seen as anti semitic. But her parents came from a time when the majority of their friends and neighbors would have been homogenous. But in Waldman’s world, in her characters’ world, race, ethnicity, and religion are irrelevant. They are topics of jest rather than ridicule. Instead, the segregating factor is class.

Wealth–and the lack of it–is constantly at the forefront of the characters’ concerns. Gentrification is observed and commented on. For instance, Nate’s street “was barren, the trees that lined its sidewalks short and spindly, their leaves sparse even at the height of spring. They had been plated a few years ago as part of an urban revitalization scheme, and they had about them a sad, failed look” (37)

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. required four and a half years to write. Waldman is awed that, by comparison, Bright Eyes, Big City was written, a rough draft, in six weeks. Partly, she says, it was about learning about writing as she went. She hopes the next book evolves faster.