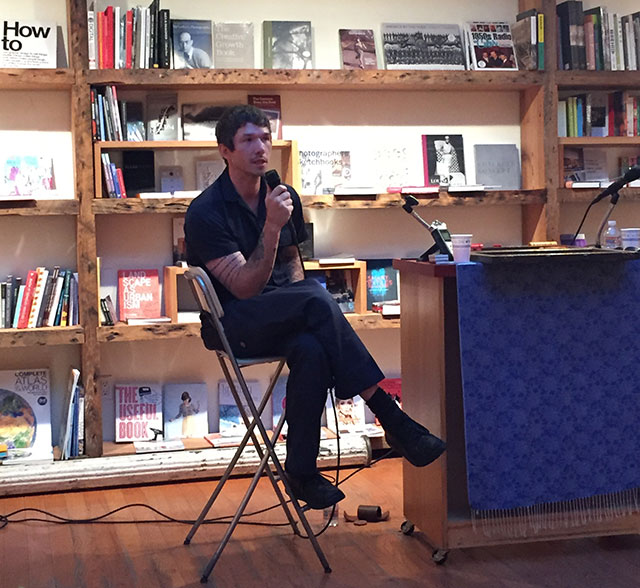

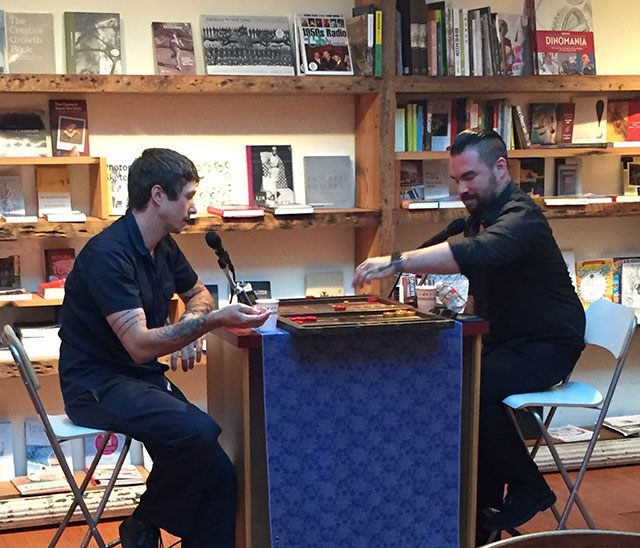

Backgammon boards were set up throughout BookCourt, the Brooklyn bookstore more commonly known for hosting literary events than board game bouts. But Jesse Ball, author motr than a dozen other books, was set to face off against Isaac Fitzgerald, Buzzfeed Books editor, while discussing his latest novel How to Set a Fire and Why.

Ball is expert backgammon player while Fitzgerald admits he primarily played the game for to win cigarettes. How to Set a Fire and Why follows a young girl, Lucia, who wants to join an arson club at her new school. As the conversation unfolded, the two played the game.

Fitzgerald might have been able to force an advantage by distracting Ball with questions about the text, but he was easily able to multiple task, often calculating his game moves while answering.

The first thing Fitzgerald asks is why Ball chose a teenager as his protagonist. Lucia is precocious and intelligent, able to observe the adults around her, but still just a teenager.

A teenager offers an ideal way of seeing the world, Ball explains. “In the world of grown people, it’s easy to become inured to things,” ball says. The voice of an intelligent child is something people can still hear–the things children say have the opportunity to be heard.

“You don’t want truth to be heard, you want it to be embodied,” Ball says adding that truth is something people don’t want to hear.

Lucia is poor, but loving. She has few friends, but hopes to have more. She lives with her aunt, and both women are nascent anarchists. Lucia reads above her grade level.

The character was created in the first page of writing. “The reason the book exists is I was curious about her,” Ball says.

Fitzgerald, who once worked as a firefighter, asks: “why fire?”

For Lucia, the fire is an anti-materialistic philosophy. Neither she nor her aunt believe in owning things, and fire can destroy objects. Fire is a weapon, but it’s not gendered. For Lucia, finding something less valuable than a person is difficult–people are everywhere.

“In the best case, writing can be like fire.”

Ball’s books take on many forms, and in a way, How to Set a Fire and Why departs from other books in that it is set in a modern, naturalistic space and time. Every book has its own needs. To write this particular book about a teenage anarchist requires a setting and place that is normalized rather than allegorical to make it believable.

“It’s not important for the book to be strange,” he says, only that the book is meaningful.

He wrote the novel during a one week period working mostly at a coffee shop. “I drank a lot of coffee.” He also listened to Gavin Bryar’s “Jesus Blood Never Failed me Yet” on repeat.

Writing is about being brave enough to fail. Ball usually writes from the beginning to end in a linear way.

“As I’m writing I’m trying to discover what she thinks and feels,” he says of his protagonist.

The arson club is something Lucia wants to belong to. Organizations are often a way to achieving what you want. However, it’s unclear if the club is filled with people excited about actual arson and setting fires, or whether they are just excited to be in a club for arsonists.

In addition to writing prolifically, Ball is known for eccentric classes. He teaches creative writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, though his classes span subjects like dreams, lies, and walking.He feels that good writing comes from reading books and a love of writing, something he can’t teach. What he can do though is teach his students become more interesting, and by doing so will make their writing more interesting.

He’s teaching a course on falsehood–how to lie better, how to identify a lie. Our culture, he says, is filled with lies and they aren’t necessarily all negative lies.

The creative process for Ball is necessary to his survival. The act of creation is the thing that motivates him and when he isn’t creating, he begins to slide into depression. Months will pass and he’ll feel terrible without knowing why and then he will write something and the fog will lift. The act of creation is the essential element, but that doesn’t necessarily mean writing is the only form. Cooking, gardening–these are all acts of creation.

Jesse Ball and Isaac Fitzgerald

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

BookCourt