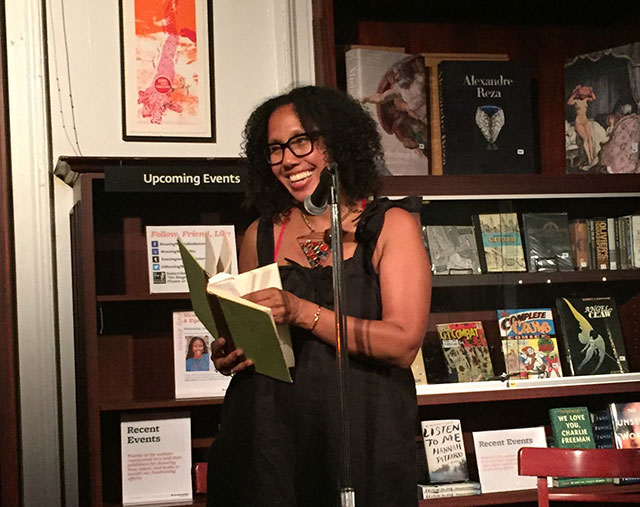

Nicole Dennis-Benn was at Housing Works Bookstore to discuss Here Comes the Sun with Tiphanie Yanique, author Land of Love and Drowning. Their discussion was moderated by Glory Edim, founder of Well-Read Black Girl.

Here Comes the Sun is Dennis-Benn’s debut novel and focuses on the lives of Jamaican women working in an opulent resort among tourists. Land of Love and Drowning chronicles three generations of a family living in the Virgin Islands, borrowing pieces of Yanique’s family history.

Yanique explains that for many years, the only way to read about island culture was through the eyes of tourists, like Herman Wouk’s novel, Don’t Stop the Carnival. These narratives were written by white visitors and islanders often became the butt of jokes.

“If I’m going to write, I need to write against this,” Yanique explains, saying she took the idea of characters from the novel and created full people.

For Dennis-Benn, her novel came about when she returned to Jamaica in 2010. She began journaling while she was there about her experiences and the journal became the book. Nobody else was writing complex Jamaican characters, she says, and it was important to make them more than flattened objects.

Yanique teaches a class on island literature, but she found that much of the literature available was all written from the outsider’s perspective. It doesn’t reflect the tourist industry workers. Partly this lack of working class literature is because what literature does come from island writers doesn’t come from the working class.

Here Comes the Sun features one woman working as a hotel clerk. Dennis-Benn says including a hotel clerk was an important character because of how a people interact with them. They serve as the hub of many tourists’ visits. They are gatekeepers to the local culture. “I wanted to give a face,” she says explaining that she wanted to explore these people and their families.

Here Comes the Sun explores sisterhood and the sacrifice. Working classes families, Dennis-Benn explains, often focus on grooming one sibling to help raise the family out of poverty.

Yanique’s family, like the family in her novel, was plummeted into poverty when the breadwinner died. The patriarch of her family was a sea captain who sank with his ship in 1926. Without his income, Yanique’s family quickly faced poverty. The age gap between her grandmother and great aunt meant one sister had received the education of a middle-class child while the other had not.

Marriage is often another way families move up socially and economically. Often these marriages don’t often leave room for love. Yanique can’t help herself from writing about love, marriage, and romance: “Deep down, I’m really a romance novelist.”

The islands are small places. There are not many people to choose from and love can get complicated. Marrying a sister’s ex-boyfriend is common because of how small the place is.

“You have to love every character you write,” Yanique says before adding, “as the god who made them, I have to love them.”

Yanique plans on continuing to write about romantic relationships. She doesn’t plan on writing genre fiction though: “when we say literary fiction, we mean good,” she says. “There is just good literature and bad literature.”

True romance novelists often end up writing in cliches or relying on formulas. “I always want to be an artist,” she says.

Writing for the Caribbean audience has grown easier. The people of the islands have access to publishers now and are starting read Caribbean literature. “I can say I write for the Caribbean first,” Yanique says.

As readers, expectations are also changing. When she was growing up, Dennis-Benn explains she was accustomed to reading white authors, especially European and American writers. When she first started writing, many of the characters she wrote didn’t look like she did.

“Writing is me finding my voice,” Dennis-Benn says.

Nicole Dennis-Benn and Tiphanie Yanique

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

Housing Works Bookstore