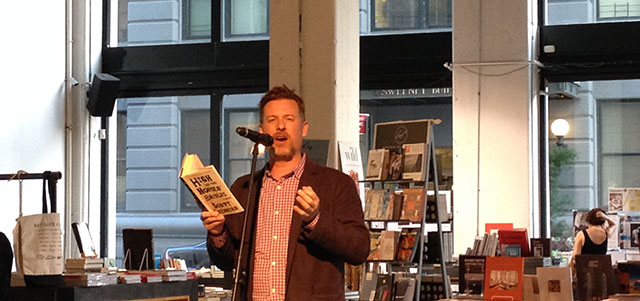

Scott Cheshire launched his debut novel High As The Horses’ Bridle at Powerhouse Arena in Brooklyn. Cheshire serves as the interviews editor at Tottenville Review. He was joined in conversation by novelist Philipp Meyer, author of American Rust (2009) and The Son (2013).

High As The Horses’ Bridle follows the story of a child prophet, Josiah, preaching about the end of the world and his awakening from the grasp of religion. Cheshire reads with the cadence of a preacher. He’s had practice. As a child, he grew up as a Jehovah’s Witnesses in Queens, with a strong religious background where he too learned to preach as a child. “I totally get why people that’s exotic,” he says, adding that within the community, those oddities are totally normalized.

Josiah’s early biography shares some similarities to Cheshire’s, though he belongs to a more generic religious sect, Brothers in the Lord. Cheshire explained that there are many different sects around the country, each with their own specialties. The Brothers in the Lord created some distance between himself and Josiah, allowing for a more honest critique.

Young Jehovah’s Witnesses are often taught to preach. They are indoctrinated early. It makes sense to push religious dogma on young people, Cheshire says. As he grew older, he discovered books. He read a lot, and that knowledge ultimately split him from the religion. His religious background also dissuaded him from attending college. “College is not a good thing for any insulated community,” he says, and he was discouraged to attend for a number of years. “It took a smart lady to say stop bar tending at Applebees and go to college.” He was an older college student when he finally attended.

For a while he found he needed to physically distance himself from the religion and his family by moving to California. “I was very angry,” he says, adding “I was happiest reading.” He eventually moved back to New York, started bar tending, attended college, and eventually earned an MFA at Hunter.

He spent ten years submitting stories to literary journals, often rejected. He also began writing the opening of his novel while attending college, though at the time he didn’t even know what a writing workshop was. The first eighty pages of the novel he used as his writing sample for graduate school. Eventually he winnowed this down to the thirty-five beginning pages. He spent time working on these early pages and realized he had created something, but to finish it, the character needed to deal with the fallout, leading to the novel.

The novel is ultimately about a character finding his own spiritual path separate from the religion he was born with. Cheshire worried about these ideas being projected on to him, and it made him anxious to think how his parents would react. His parents are still religious, but the novel was well received by them.

The novel develops around the idea of the prophecy of the end of the world, a premise Cheshire finds compelling. The end is less about destruction and more about complications of time. Its about realization that time is finite and that not everything is moving toward something grand. Its about learning to live in the now and in the moment, Cheshire says, something he had to grapple with understanding himself.

Cheshire says he ended up writing a novel rather than a memoir because he lacked the distance to treat the subject properly. “I was just trying to write too objectively,” he says. He ended upjudging the people he was writing about too harshly. Fictionalizing the account provided the distance he needed to be both more generous and more judgmental, but in a better balance.

When he first started writing, he was just making stuff up. He invented everything and drew nothing from his own experience. “I was just making crazy stuff up,” he says. Eventually in graduate school he learned that better writing pulls from original experience. Everyone’s version of basic emotions are experienced differently, and truthful writing relies on the universality of those emotions to attempt to experience them as the author does.

Scott Cheshire and Philipp Meyer

Powerhouse Arena

Tuesday, July 8, 2014