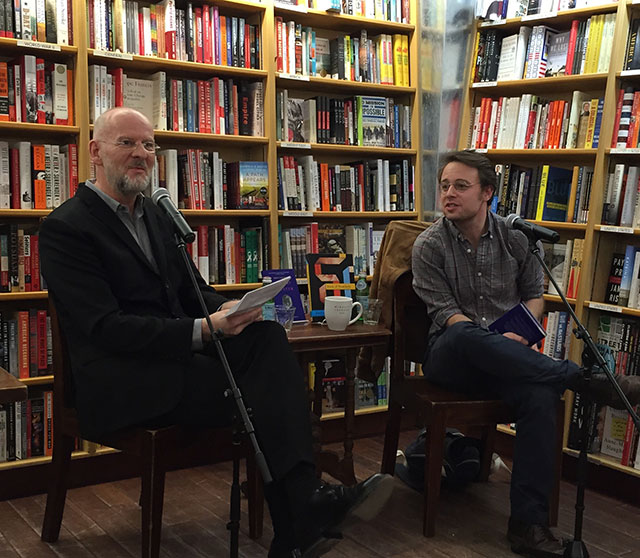

Simon Critchley is a philosopher and professor typically writing on political theory, ethics and aesthetics. His first novel, Memory Theater, does not stray very far from those topics. He was at McNally Jackson Books to discuss the novel with Joshua Cohen, author of Book of Numbers.

Cohen describes Memory Theater as a forceful book about memory where the ultimately goal is total memory.

“Writing is the enemy of memory,” Critchley says, because people write to not forget.

The protagonist Simon Critchley is rather similar to the author: similar jobs, resume, works published. Within the novel there are plenty of things the real Critchley cares about such as gothic architecture. Gothic cathedrals, he explains are a lot like memory palaces. The entire sum of what can be known are organized spatially within the buildings. This form is the essence of a memory theater: a physical system of displaying memory.

The internet serves as a modern memory theater. It is a code for organizing our reality. “We don’t believe what’s in our heads anymore,” he says. We are always looking up a fact on the internet.

Cohen asks why Critchley chose fiction as a form to deal with these issues rather than essays, especially since fiction is a subjective experience.

Some people say it is all fiction, Critchley responds, since even essays involving making shit up. He laughs. To him, writing fiction still means that everything in the book exists and can be substantiated. He wants a high bar for his writing.

In teaching philosophy, he must lay out different systems of thought. Teaching requires students to understand both Descartes and Spinoza, but to be a philosopher requires accepting only one or the other. Both must be fully understood, and students must be fully seduced by them before rejecting one or the other. Critchley says that one way of dealing with philosophy is a kind of writing that denies its written status.

Philosophy is often most successful through indirect forms of communications. Many people think there is an answer, a truth. Truth is not found by eliminating interpretations but instead by having more interpretations.

For instance, Greek tragedies are plays that have at least two interpretations of the world. The plays are the presentations of these conflicts in meaning. Presenting multiple meanings shows a greater truth than presenting only one.

“People will be sucked into sad and grandiose systems,” Critchley says. Reading presents you systems so that the reader can watch them fall away.

Simon Critchley and Joshua Cohen

Monday, November 23, 2015

McNally Jackson Books