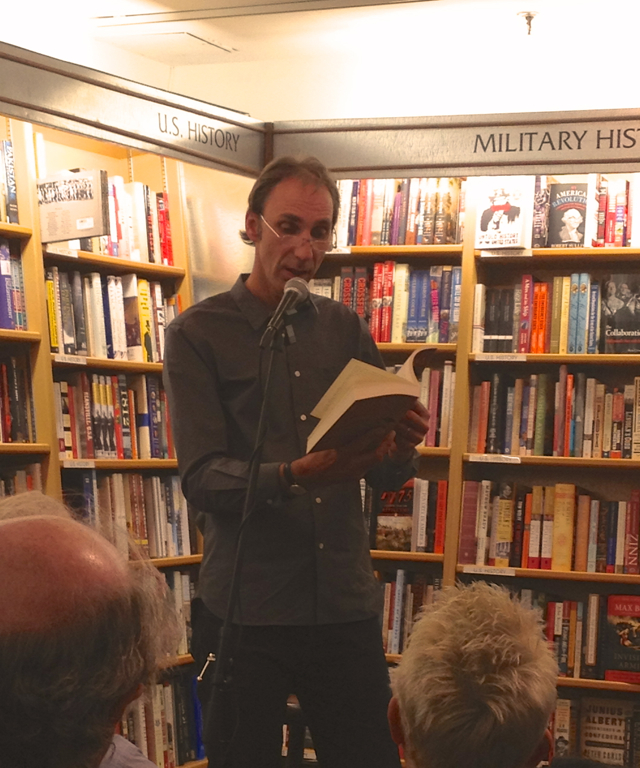

Two giants of modern British literature came together to discuss their differences and read from their recent novels. Will Self, who is also a literal giant, read from his latest novel, Umbrella and Martin Amis read from Lionel Asbo.

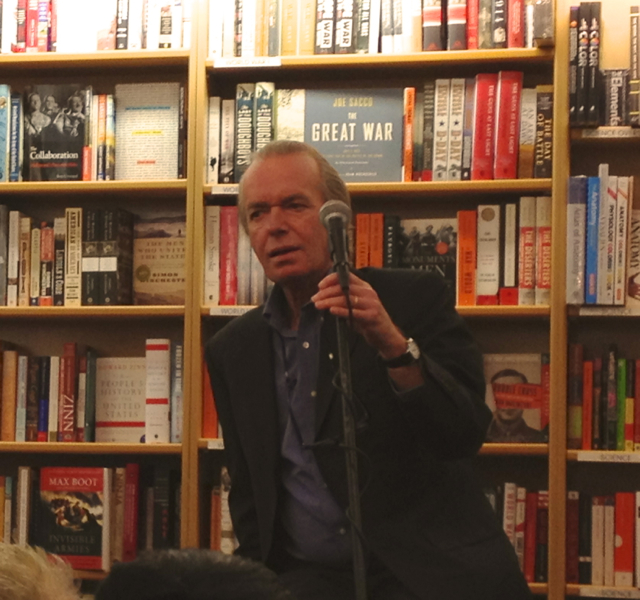

Amis began the evening by describing their pairing as the coming together of opposites, like pairing Jorge Luis Borges and Joyce Carol Oats. But, Amis adds, opposites sometimes attract.

The two men offer quite different styles. Self seems to scoff at ensuring clarity in his work professing an interest in leaving many readers confused while Amis says, “there should never be any doubt of what’s going on.” The structure of their sentences are different too with Self preferring long paragraphs often lacking even in breaks for punctuation While Amis wants room, saying “the novel needs air.”

But Self challenges the notion that they are opposites. They are both English, male writers after all. And then, meant as a compliment, Self declares that like most English, male writers, he endures a kind of anxiety of influence from Amis. He describes the feeling as the “horny skin of your palm caressing our efforts none too gently.”

The point of difference Self does acknowledge between their writing is in a metaphor of pilots: “what you want is a for a novelist to be in a control tower directing the planes, not running around on the runway.” Self describes his novel by what it lacks: no chapters; no speech marks; no constructed metaphors; nothing with any similitude; and finally, no apologies. Specifically, Self says that he makes “no apologies to readers who may not know what’s going on.”

[pullquote]”I wrote for the one reader.”[/pullquote]

The reader is important to Self, just not all readers. He refuses to be governed by their wants, instead saying, “I wrote for the one reader.”

Amis agrees in a way that there is an ideal reader, and its not always the commercial audience. Nothing good has ever been written, he explains, when its been written for the commercial reader in mind. That doesn’t mean, however, that some writers don’t fall out of love with the reader. Amis says James Joyce and Henry James both “obviously” did.

Reviews should be ignored, Amis warns, because most say very little. He has contempt for reviewers, who it would seem, are not his ideal reader. “The only value judgment that matters is given by time,” he said, though also adding the caveat that writers can never know the results of this kind of judgment as they will be dead.

Self adds that the collapse of the literary culture might render moot that kind of judgment anyway. There seems a moment where both men are conscious of their ages and the shift in cultured society, before they decide to transition to reading instead of mourning.

Amis reads first saying he would keep it short knowing Self will take his time.

After reading, the two authors took questions from the audience. The very first question is of Self’s use of language as a metaphor, seemingly breaking his rule that the book does not have any. Self clarifies saying he avoided constructed metaphor, and then taught everyone in attendance, including Amis, a new literary term: metaphrand. The metaphrand is the object or concept illuminated by the metaphor. Self explains that metaphorical language isn’t the problem, but instead those metaphors that are ornately constructed, somewhat derisively describing them as the work of a creative writing MFA.

An audience member raises the question of ideal readers asking who the authors believe their ideal reader is. Self begins by describing his ideal reader as at once intimate with his work and also distant. There is no specific demographic that this ideal reader is, only someone with that kind of synergy. Self has a world view he wants to express, and his ideal reader will be one that understands that.

Amis offers, “I imagine myself at twenty-one or twenty-two and my ideal reader feels the same way I felt reading my first Bellow novel,” he says, explaining that its the sense that the author is speaking directly to him that he wants to achieve.

The thing about ideal readers, Self says, is that readers are not monogamous with writers, and “most of us only love a few works.”

[pullquote]”Even when we say we love a writer’s work…we only love about half of it,”[/pullquote]

“Even when we say we love a writer’s work…we only love about half of it,” Martin adds. Both authors then admit to having only read about three-quarters of the others’ body of work.

The state of literary culture seems to be of concern to both men. Self declares that the novel will no longer exist in a generation or two, blaming shorter attention spans and wireless devices. He believes the climax of the novel was in the middle of the last century, but then posits, “why shouldn’t it change?”

Amis believes novels will continue on, but will be a minority interest pursuit rather than mainstream commercial enterprise. Literary culture, as it exists or at least, as it once existed will come to an end. There will be no parties or book launches or photo opportunities he warns. He disagrees that the novel peaked mid-century, but rather sees a boom beginning in 1980. He ponders that perhaps this period was the anomaly, rather than any grand literary history.

[pullquote]”people’s demand for narrative is insatiable,”[/pullquote]

Self adds to this, saying, “people’s demand for narrative is insatiable,” but those narratives must change. The novel is a relatively new form, and just as other forms of literature have evolved, so should the novel. The audience is now thoroughly depressed.

Someone asks how the authors know they have completed their sentences, at what moment they are finished.

Self describes a kind of feeling, one that seems mystical in origin as he offers no concrete specifics. For him, its just a sense of completed-ness. And then he jokes that often he is finished because he needs to send something to the publisher, speculating he might have been a very different writer if he had an alternative source of income.

Amis provides a somewhat more serious assessment. He is concerned with phonetic variation, with the rhymes and cadence, and ensuring that each is there intentionally, or removed. He describes the process as “the flushing out of inadvertency… I keep looking at my sentences until nothing snags on my ear.”