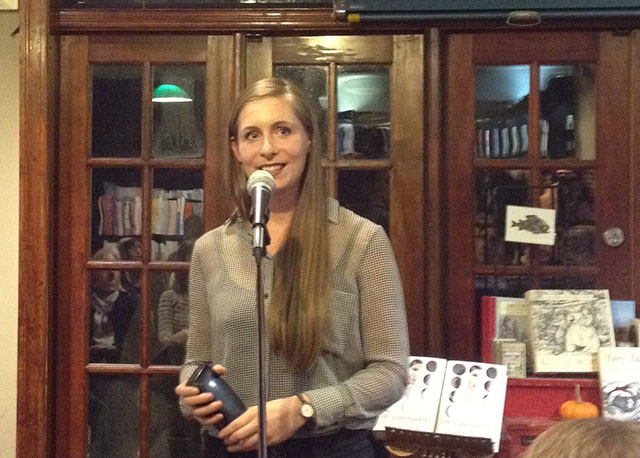

Eleanor Catton, author of the The Luminaries and recipient of the 2013 Man Booker Prize winner read from her novel at Community Bookstore. The novel, set in in 1866 New Zealand during the second gold rush, follows a tight structure linked to the signs of the Zodiac. The story unfolds during twelve days throughout a year, each corresponding with the zodiac periods, while twelve characters, also linked to astrological symbols, find themselves caught in a murder mystery.

Catton read a segment of the novel that highlighted her humorous narrative voice, clever in its wit. After reading, Catton began taking audience questions, threatening to lecture the audience on astrological signs if they failed to ask any questions.

Catton started off explaining the origins of the idea of the novel. She had been thinking about the word “fortune.” It can mean a great of money, but also can refer to uncontrolled fate. It seemed a kind of duel meaning that she could enjoy. She says too that she was “fascinated with what it means to be a self-made man.” New Zealand’s second gold rush occurred in an area of thick rainforest, an inhospitable place. But Catton points out that she finds it strange that someone can walk into the jungle and pick up a rock and be considered a self-made man.

Plenty of research went into the novel. In addition to the gold rush history, Catton researched the cults of the 19th century, and she read a lot of Carl Jung. Astrology, she explains, is a lot like primitive psychology. She also read classic Victorian era novels, citing George Elliott and Russian novelists of the period. These she read as a way of setting mood and tone; her goal was in capturing that victorian novel sensibility. And she read 20th century crime novels. She wanted to figure out what crime and mystery stories she enjoyed and what she liked about them.

Catton saw the signs of the Zodiac as emblematic of western thought, and wanted those figures as real people. Her first inclination was to have all the characters come together as a jury. She was well into writing that book before learning juries can’t meet in secret. She seems almost embarrassed that she allowed such a mistake. But then she came around to having all the characters accused of the crime.

The symbols all relate to their characters. The banker is a Taurus because its a wealth sign; cancer is of the hearth, and thus an inn keeper. The thirteenth character is a stranger and acts something like a detective.

The pattern took a lot of time to work towards. Catton made her own star charts to consult, though by now it seems her knowledge of astrology is deeply ingrained. But she adds, that once she found the structure the novel came together well. She says her knowledge of the astrological signs “sounds deeply insane,” but these limitations helped define the novel. She preferred the restrictions to using a blank slate with unlimited possibility.

Relying on the Zodiac signs provided her work a framework. She describes given writing prompts for her students. When she has open ended writing prompts, the students turn in identical poems drawn from what ends up being a very similar, limited vocabulary pool, with very limited creativity in structure of poems. Yet, when she forces them to work around a problem, they produce better work because they are trying to solve each prompt in a different way. Relying on the astrological signs as structure achieved the same thing for her. “I had to think outside of the box,” she says.

Asked if she would structure her next novel in the same way rather than begin with a blank slate, Catton seems unsure, but then adds, “I don’t want to repeat myself… there is no system quite like astrology.” She recently met Yann Martel, author of The Life of Pi and 2002 winner of the Man Booker Prize. He told her to wait two years before writing anything else, to enjoy the time, and she seems relieved of the burden to write anything at the moment anyway.

[pullquote]”I’m happy to be called a fantasy writer.” [/pullquote]

A member of the audience says reading The Luminaries feels like being told a story, and Catton jokes she tried calling it a children’s novel. But more seriously, she adds, “I’m happy to be called a fantasy writer.”

The novel is tightly framed around the twelve days. For Catton, she saw her problem as many novels with tight structures are beautiful, but often lack plots. She wanted to create something with both plot and structure combined together. It was important to fuse those two ideas.

Often, Catton’s age — she’s the youngest winner of the Man Booker yet — becomes a descriptor when things are written about her or her books. Interviewers ask about her age, as do the audience members, in ways that seem to marginalize her talent. She describes the characterization as “frustrating,” mostly because her age is something she has no control over.

Catton recalls some of the early reviews of the book in New Zealand. Two of the reviews had made reference to the novel as bodice rippers, as a not particularly worthwhile book to read because it struck them as too genre. Catton attributes both reviews to her age and gender. She laughs though, saying she couldn’t help but point out the reviewers were both old and male, implying their own time has come and gone.

Catton seems to have at least some belief in astrology. She says she is very good at guessing authors’ signs, although she also jokes that smugness is a Libra quality. (She is a Libra). She adds though that she thinks there is probably some truth to ancient systems like astrology. She says jokingly that she wants to work on a series of essays pertaining to authors and their zodiac signs — critical essays looking at their astrology. She describes it as Astro-Criticism, and the impression she leaves the audience is that she is not actually joking. Both editors who worked on the book with her were Virgos, she adds.