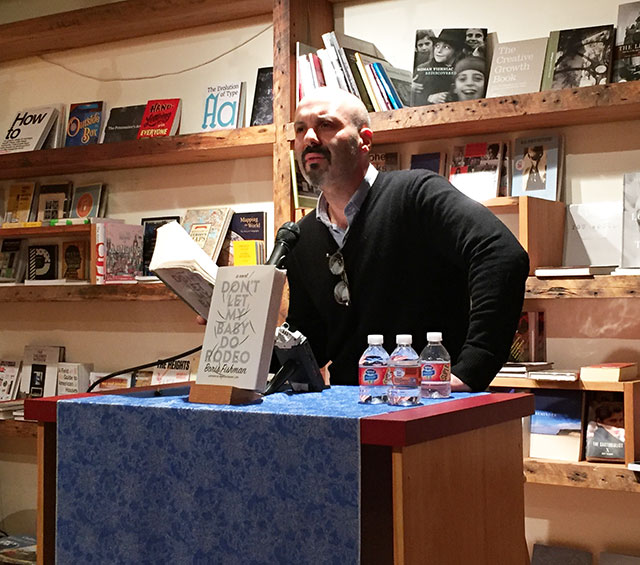

Boris Fishman presented his sophomore novel Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo at BookCourt in Brooklyn. His debut novel, A Replacement Life, explored male family relationships through a son and grandfther’s attempt to defraud the German government of holocaust reperations. His new novel dives into the relationships of women.

Maya and Alex are former Soviets living in suburban New Jersey. Unable to have biological children, they end up adopting an American baby whose mother leaves them the cryptic message: “don’t let my baby do rodeo.” As their child, Max, grows older, he begins acting out, and Maya and Alex must seek out answers to their son’s past.

The adoption of an American child by Eastern Europeans is a reversal of a common trope of Americans adopting Eastern European babies. Alex and Maya ultimately are ill equipped to deal with the problem with their family. Fishman observes that in places like the Soviet Union where there was a lack of things, there is a great deal of desire for things that are new. This desire extended to people, including children. Adopted children were seen as castoffs.

Fishman explains that in his family there was a lot of self-repression. In writing A Replacement Life, Fishman took inspiration directly from his own experience. When he set out to write the second book, he wanted to move away from that instead looking at the lives of his mother and Soviet women. He says that the gender equality of the Soviet revolution meant women simply had two jobs instead of only one and that to survive, their response was to be amazing.

Soviet women define strength, Fishman says, and their idea of womanhood is different than their American counterparts. He describes that difference as the gospel of self-obliteration. They are willing to sacrifice everything about themselves for their family. However, that sacrifice also relieved them of the obligation to look inwards towards their own wants and needs.

Writing Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo was a kind of exploration of a fantasy Fishman had. He wanted to know what his mother would want if she were honest with herself, if she were not, in the tradition of Soviet women, focused on self-sacrifice. Fishman explains by way of example. His mother has always loved flowers and he often buys them for her in the flower district. One of his usual venders agreed to allow for his mother to come to a shop to learn how to arrange flowers. She went only once. She has, he says, a kind of internal resistance to self-fulfillment. She stopped because she insisted that she is too old to change. So Fishman gave up on trying to get his mother to change, and instead created a character.

Montana plays an important role in the novel. Its also played an important role in Fishman’s life. The state is central to a personal story of his, one that he describes as the story that got away from him. As a child living in suburban New Jersey, he saw the film Legends of the Fall. He adored the film, and he felt a strong connection to the idea of how Brad Pitt fit in with the landscape.

Five viewings later, he learned that the film was actually first a novel. He found his way to a bookstore and purchased the book. A new book was an extravagant purchase given that it cost as much as five hours of his grandmother earned washing floors. But nevertheless, he bought the book. His main take away was that he wanted to live in a place like that and write a book like that.

For years, there was no way for Fishman to explore his curiosity. He held onto that ideal though, and eventually found himself applying to graduate programs in Montana. He visited the state as part of the application process. Perhaps surprisingly, the magic of Montana lived up to his expectations, something he says is rare with our curiosities.

He remained in New York City for school, but the following summer found himself heading back across the country. This time he was stalking Jim Harrison, the author of the novel Legends of the Fall. He found Harrison relatively easily by simply knocking on the man’s front door and ended up spending a few days with him. After that meeting, Fishman returned to New York and wrote the first novel filled with inspiration from Montana.

Fishman’s love affair with the state isn’t over. This summer he is headed to a farm there looking to work the land and explore the possibility of relocating there.

The myth of the west has died, Fishman says, and rightfully so. However, for the immigrant, it still persists. “There is room to inscribe yourself here,” he says of Montana.