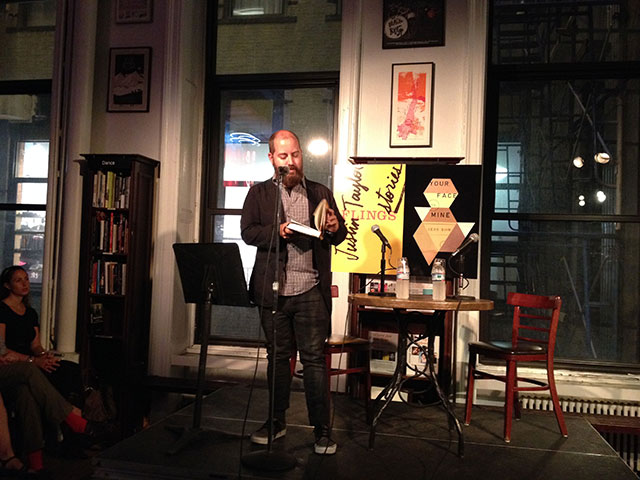

Justin Taylor’s new collection of stories, Flings, traverses the globe with disconnected characters. Jess Row’s new novel, Your Face in Mine follows the story of Kelly Thorndike’s return to his hometown of Baltimore where he meets a former childhood friend who has undergone racial reassignment surgery, becoming a black man. The two met up at Housing Works to talk about the construction of place and setting in fiction.

Taylor read a portion of the story “The Happy Valley,” following a girl in Hong Kong who ends up at Jewish cemetery of the same name. The places are real, and Taylor even began conceiving of the story as an essay. Row read unconnected portions of his novel choosing scenes that focus on descriptions of Baltimore. Though Row’s novel is set in the Maryland city, both writers have spent considerable time in Hong Kong, and Row’s earlier novel The Train to Lo Wu (2005) draws inspiration from his time there.

Taylor has spent several summers in Hong Kong visiting with family members who have been living there full time. Before ever having met Row, Taylor says he picked up a copy of The Train to Lo Wu, Row’s book about a Chinese girl and an American teacher exploring Hong Kong. Row also lived in Hong Kong for a number of years.

Row says he first imagined himself like Hemingway–an expat writing about places like the midwest from a distant hotel room. He was living in Hong Kong then trying to do just that when he had, what he describes, a complete artistic breakdown.

Writing about Hong Kong proved more difficult than he expected. He didn’t want to look at the city as a “buffet of exotic experiences.” At the same time, he struggled to write about his hometown of Baltimore. Only after watching The Wire did he find the story he wanted to tell. At one point in the television series, the police are driving out of the city center into the greener outer, more suburban districts of the city. Though only ten minutes apart, these two neighborhoods could have been continents away from each other. Row says he wanted to capture that disparity between places and the tension that exists.

Taylor, as visitor rather than resident, had a slightly different experience in Hong Kong. He was both a tourist–he got his passport for the first time to go–but he also lived the day to day life because he was staying with family. He stayed a month or so at a time, but before writing about the city he also wanted to explore the things that had already been written about it. He had intended to write non-fiction essays about the city. He started writing some things but couldn’t find markets to sell the essays. “I had a bank of experiences,” he says. And then he turned those into stories.

Of Flings, he says its all the material he had been working on about Hong Kong. “This contains every single thing I know about Hong Kong,” he says definitively.

Time is as important as geography when constructing place. Row says that Bangkok, for instance, is very different today than when he was there. Of course, he adds, “you’re writing about one kind of subjective experience.” Its not that something isn’t accurate, but that it is personal.

The western experience of Thailand, Row continues, comes with a conception of a place where anything goes, anything is permitted, a place of endless possibilities. Its like the ultimately wild west. But that kind of idea only exists because tourists are catered to. The day to day life in the city is opaque to tourists.

Whether in Hong Kong or Bangkok, the western experience is tainted by access to money. Finance expats have changed Hong Kong, Taylor says. For a lot of them, it was a chance to get away from the recession of the late aughts. Parts of Hong Kong even shared in that kind of enthusiasm. But that meant altering Hong Kong and warping it into what their perception of city should be–and Taylor adds, the same thing is happening to New York.

“The world of finance creates the kind of bubble wherever it lands,” Row says, describing the effect as bringing a sense of sameness to disparate places.

Row shifts the discussion to Taylor’s characters who he describes as drifting. He adds that many of the characters fail to change, or if they do, only a slightly, subtlety.

Taylor explains that he became interested in the notion of duration. Sometimes endurance has its own kind of narrative that is more important than a character evolution. Distance in time changes perceptions of an event. Things that persist have a narrative different from things that change.

Race plays a significant role in Row’s novel. The result has been people asking him about race, and what it means to have an authentic racial experience. “I don’t have a good answer to that,” he says. “Authenticity is something that is reinvented moment to moment,” Row explains, adding that it is something that renews itself.

In college, Row says, he was really interested in American Realism as a movement. When he moved to Hong Kong, his first instinct was to try and live out some kind of white authenticity there. For him, informed by mid-century realist literature, he interpreted that experience to mean a lot of whiskey drinking. Stories he wrote involved a lot of long silences and deep thinking. All of it felt like “white drag,” he explains, as a white male author. Eventually, he learned to write about race. In Hong Kong, he explains, it was very easy to understand signifiers of authenticity as commodified.