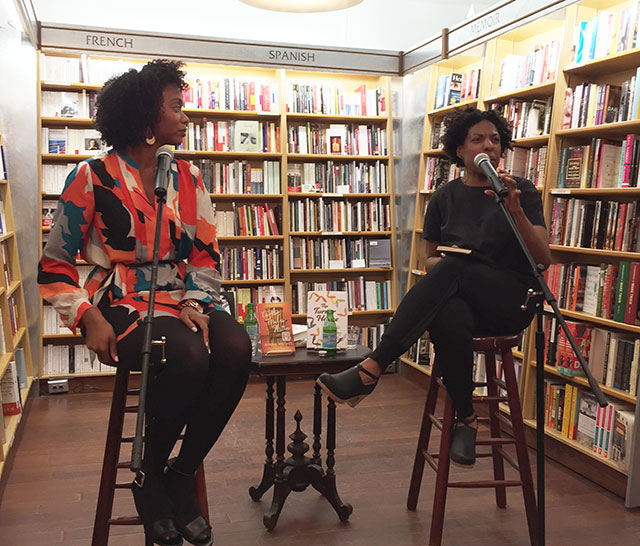

Thirteen children were raised in the Turner’s Detroit home. The decline of the city has meant that the house is worth less than its mortgage and as the aging family matriarch is forced to leave and her children must decide the fate of the house they grew up in. The Turner House is Angela Flournoy’s debut novel, a family epic. She read from the book and discussed it at McNally Jackson with Ayana Mathis, author of The Twelve Tribes Of Hattie.

Detroit is more than just a place in the novel. It serves as an essential element. Still, Flournoy says there are parts of the city that only exist in novel. Yarrow Street, where the Turner house sits, is made up. She rearranged the city as was necessary to fit the story. She moved some locations from the west side to the east side, for instance.

“I was interested in the facts as it was pertinent to the characters,” she explains.

Few novels are set in Detroit–unless they are a crime novel. Flournoy says she took the setting very seriously and that it is a city defined by its persistent housing discrimination. There was a rapid and total abandonment of the city, a shift that occurred in one generation. Wealthier, whiter people just vanished, and along with that, the American dream for the rest of the city.

Mathis points out that throughout the novel, there is a thread of silence.

Silence has to do with a combination of pride and shame, Flournoy explains. The family is prideful, but also fears shame. That creates a fragile sense of pride. For the contemporary generation, that leads them all to want to be the ideal sibling. Flournoy says that her experience growing up with four large families serves as the model she drew inspiration from. For a family this large, outsiders always want to know why the family is so large.

Flournoy says that most of friends no longer live in the places they grew up in so they are less connected to their families. Her family has scattered too, and once they stop living in the same time zone, are much less linked together. The result is construction of new families around friends. Friends, she says, influence her a lot more than her family because she ends up seeing friends much more often than she sees her family.

The other difference is how people perceive friends. Friends can end up leaving. There is a time when they were not part of your life, and so there is an idea that those relationships can end. With family, there is always the sense that there will be a second chance. There is always the possibility to reconnect.

Flournoy says that having a large family lead her early in life to understand social hierarchies. It was important to know who to say “hello” to first when entering a room filled with people. That makes it easier to prioritize point of view and create the right psychic distance from her characters.

Writing a large family is about balancing those character point of views. Some siblings have a lot of page time, but aren’t necessarily very intricate to the novel other than to serve as a plot device. Some of the siblings had to have subplots cut. The challenge was focusing on the primary characters and allowing the tertiary characters to be less domineering.

In beginning the novel, Flournoy says she felt lucky because the early scenes she wrote produced no answers. She only had questions that needed to be answered. There was a scene that she wrote and workshopped that included a text message argument. One of the criticisms was that the character was too old to be text messaging. Flournoy didn’t think forty was too old to have text message argument.

“I only think about one character from the book anymore,” she says.

She also says that her next book definitely won’t be in Detroit. She’s looking at five other cities instead.