Caleb Crain’s first novel, Necessary Errors, released last week, has received mostly high praise in book reviews. Slate went as far as calling the novel a “new model for contemporary fiction.”

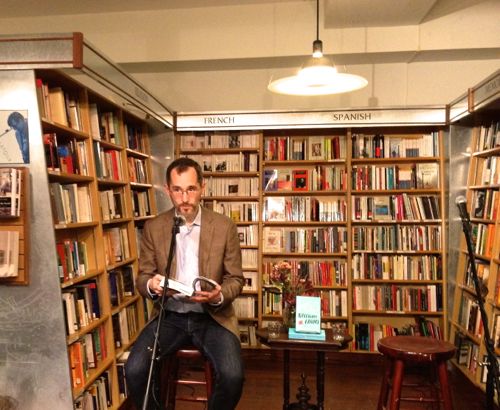

Lorin Stein, editor of The Paris Review, joined Caleb Crain for a reading and discussion at McNally Jackson Books.

The novel follows a group of friends, Americans, living in a bohemian Prague in the mid-1990s. This is not an unfamiliar trope for gen-x, and is indeed the premise of Arthur Phillips’s 2003 novel, Prague. Aaron Hamburger, in the New York Times describes the period: “In the immediate aftermath of its nonviolent Velvet Revolution, during which the Czech Republic transitioned from Communism to democracy, Prague was filled with young American adventurers like myself who’d come with plans of making various forms of art, though mostly what we did was hang out. We’d been seduced by the promise of cheap rents, cheap food, cheap beer”

Crain read a section of the novel where the protagonists faces the imminent slaughter of a pig before bowing out. It seems both strange and foreign all at once, and setting the novel in the 1990s, before the internet and cellular phones in a place that seems foreign is the point.

The first question Lorin Stein asks pertains to Slate’s characterization of the novel as a “new model” and Stein’s own interpretation of that as being “not normal.”

Crain explains he always saw himself and the text as a little bit weird. He references his novella as another example of his own strangeness: he began that by writing dialogue, and so its dialogue heavy. His intent was to move away from that, but Necessary Errors, also ends up heavy on dialogue. That, he sees, is part of the strangeness. He suggests perhaps its the influence of mid-century authors like Henry Green.

Though the characters end up discussing politics, Crain never intended it as a political novel. Instead, its about young people who take themselves very seriously. When the characters talk about politics, it is more about hinting at motives or plot rather than the issues themselves.

And though the novel relies heavily on dialogue, especially with characters in large groups, Crain carries off the narrative naturally. Stein mentions that in an early draft that Crain showed him, often characters announced their arrivals and departures in dialogue. Ultimately though, Crain skillfully managed these group conversation situations so that they flow smoothly.

Crain explained that he hears his characters speak in conversation making the distinctions in voice and rhythm, even in large groups, evolve naturally. When the voices don’t flow, he knows he’ll need to rewrite the scene. He also notes that any outside conversation, even when he cannot hear the actual words of a conversation, merely the cadence, he is thrown off. He works in silence.

One of the challenges with these conversations was in instances when the characters end up talking about writing. Crain wanted to impute pretentious attitudes on the characters, but not a pretension from from “the novelist;” that is, the characters, writers in their early twenties, might sound a little pretentious, but he didn’t want any sense that these moments were his own voice speaking about writing or the process.

Stein asks Crain what differentiates his novel from normal novels, what is it that makes it weird or strange or stand out.

“Novelists always write the novel they want to read,” Crain says. There is a frenetic tone as contemporary novelists deliberately search for plot twists and end up avoiding the real problems of real people. His examples of real problems include: age, not being loved by the people you love, not making enough money, not knowing how to do something you want to do. Instead, many contemporary novelists end up finding odd, esoteric plot problems creating characters who are impossible to relate to.

Crain spent seven years working on Necessary Errors. He never really revealed to people that he was working on the novel until he came to the end. It felt to him like “you’re an adult and you’re playing.” He compares novel writing to playing in a sandbox; now that the novel is finished, he doesn’t get to play in it anymore.

He wrote the novel sequentially from an outline. He realized he was finished because he had come to the end of his outline. And though he finds the praise his novel has so far received rewarding, the real pleasure came from writing itself. “Writing was like a drug.”

Caleb Crain

McNally Jackson Books

Monday, August 12th, 2013