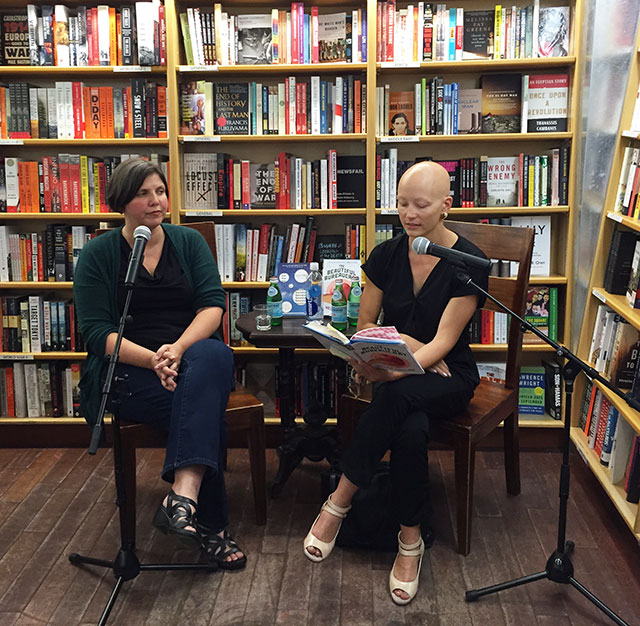

Helen Phillips was at McNally Jackson books discussing her debut adult novel The Beautiful Bureaucrat with Jenny Offill, author of Dept. of Speculation. Phillips previously published the short story collection And Yet They Were Happy, as well as a children’s adventure book Where the Sunbeams are Green.

Phillips was working at a university in an administrative position when the title of the book came to her. Each year during admissions, she would input data about prospective students and she began thinking about the people that data represented. Another eight years would pass before she finished the book.

The title has a second meaning, one more accidental than intentional. Phillips searched the internet for the phrase and found that Allen Ginsberg actually referred to Kafka as the The Beautiful Bureaucrat in a letter. It was purely a coincidence, although a happy one.

When Phillips set out to write the novel, she wanted to create a book that merged the ambiguity of image and abstraction with the elements of thriller and plot. She would want to call it a poetic thriller if she didn’t think her publisher would be afraid of the word poetic.

“I think it is a real accomplishment to write something that gets you to turn the page,” she says.

The protagonist of the novel works in a large building. She is, after all, a bureaucrat. Offill points out that often it can be a challenge to write about dull things without the dullness coming out in the text.

“I did write a very boring draft of this book,” Phillips acknowledges. The earlier draft was two-hundred pages longer. She said she wanted to be precise with the language. When she was pregnant with her daughter she had a nine-month window. Her agent read the draft though and said it was too bleak and dark.

A year later, adjusted to motherhood, Phillips re-read the book. She explains she was very close to not finishing it. Only after she was committed to a new draft was she able to start cutting out excessive text. To keep the pacing fast and prevent the dullness of bureaucracy from crowding out the book, she allowed herself to keep one sentence from each paragraph about the office during the edit.

One of the challenges of the edit was working full-time with a young child. She wrote for one hour segments every day. But she credits that limited time with producing a better draft.

The book contains lots of wordplay. “I’m always concerned with language and wordplay.” Phillips describes these twists of language as simply the way she thinks. She adds that children often have a playfulness with language as well.

The book is set in 2013, although some people have described it as dystopian. Phillips explains that twisting something a little reveals the darkness. “I’m always interested in the sinister underlying the mundane.”

Phillips writes from the images that come to her. She describes the process as not a good way to write. She writes about the images that intrigue her, and then connects them, even if they are not inherently related.

“Story grows out of images,” she explains. It was only in the sixth year that she found the story and plot.

“I’ve been a little bit scornful of plot,” she says.

“I went through this period in Brooklyn where I saw so many dead animals,” she says. So in an early draft, there were a lot of dead animals littering the manuscript. She edited all but one of those out.

Phillips sees writing as a moment of exposure. “Its such a private thing,” she says, adding, “It feels like my soul is on the line.”

That sense makes it more difficult to read reviews. The New York Times review found a lot of symbolism that Phillips never intended. She points to the office number, 9997, that the reviewer thinks is a reference to the devil’s 666. Phillips says she just wanted a high floor in a nondescript place.

Phillips isn’t writing for the reviewers though: “I think that what keeps me going no matter what, I always just enjoy and find rewarding the process of writing.”

Helen Phillips and Jenny Offill

Monday, August 11, 2015

McNally Jackson Books