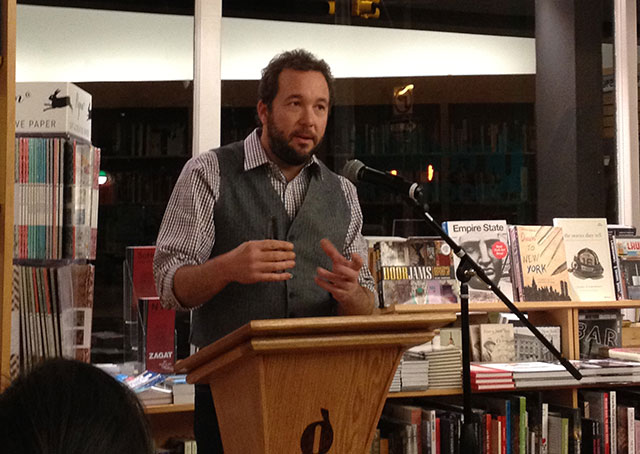

Jonathan Miles launched his second novel, Want Not, at Greenlight Bookstore last night with a reading and questions from the audience. He is also a journalist and his first novel, Dear American Airlines (2008), garnered praise.

Before reading, Miles told an anecdote about Berlin. He saw a sign at a bar advertising shot specials like Kamikaze and Sex on the Beach. Last on the list was a Brooklyn, a stodgy, classic cocktail seemingly out of place alongside spring break mainstays like Sex on the Beach. However, when he investigated, he found that the Brooklyn special offered at the bar was actually a Manhattan, thus he quipped, demonstrating that Brooklyn had indeed surpassed Manhattan in global cultural cachet.

Want Not is a novel of three narratives. Miles describes the narratives as linked together like the symbol warning of radiation. The structure allows Miles to explore the lives of three disparate characters: freegan Micah, David and his wife Sara, widowed on 9/11, and Elwin, a linguist tasked with crafting a symbol to warn future generations of nuclear waste stockpiles.

Miles reads two sections. First is David, the New Jersey debt collector who has begun noticing his daughter’s budding sexuality. He then reads from Micah, the freegan, discovering the wastefulness in the world. Miles is funny and well practiced in his performance. The narratives are written to be humorous too, as much in the interactions of the characters as with the narrative voice.

After reading, he describes how he started off writing about Micah. There wasn’t necessarily a conscience choice to write multiple storylines. “Choosing [to write] three stories is crazy,” he said, but the novel evolved naturally that way. He describes Micah as having started the party, creating interest in the world that Miles then wanted to bring other characters to.

In order to gain perspective on Micah, the freegan character, Miles explains that he spent time hanging out with the freegan community. “It is stunning what you find,” he said of the experience. Grocery stores throw away plenty of products that are still fine.

One of the freegans he came across loved the detritus from steam tables at deli food counters — the hot food tables in bodegas. “That was tougher than I could go,” Miles says, because all the food mixed together. Still, the freegan who showed him the food pointed out that it all ends up mixed together in the stomach anyway.

[pullquote]”All civilizations end up as a landfill.”[/pullquote]

The most difficult character to write was Elwin, the linguist. Elwin is responsible for inventing a symbol warning of nuclear waste that can be coherent and understood ten thousand years into the future — a real project being undertaken by governments around the world. No language has survived ten thousand years, the half-life of much of the radioactive waste that governments plan on storing as a bi-product of nuclear energy and nuclear arms. The symbol is meant to transcend generations and the loss of all modern languages. “Its a wild and depressing thought that the only thing left in ten thousand years is a trash dump,” Miles says, “All civilizations end up as a landfill.”

Yet, the hard part about writing Elwin was not the apocalyptic finality of humanity, but that the character’s father suffers from memory loss and alzheimer’s. Miles admits his own mother endures the disease, making it personally difficult for him to write about it.

[pullquote]”You can’t disappear anymore … there is no frontier”[/pullquote]

Miles might be one of the few authors to tackle freeganism as a novelistic plot point. he says that while the waste society produces is shocking, freeganism is not really sustainable because its merely picking up waste. American society is still very wealthy, but eventually will become more efficient and produce less waste. The true nature of freeganism is less about picking up waste and more about living off the grid. The people he met are primarily dropping out of capitalism, the equivalent of starting over by going to a distant place like Alaska. “You can’t disappear anymore … there is no frontier,” he says.

Writing the book required five years. Though he began it in a period of economic despair, during the great economic crisis, he says the economy shouldn’t affect a novel. The United States was still in a period of hyper-abundance, and there was still plenty of waste for freegans. “We are living in an age of incredible abundance,” he says. He admits too that the whole experience researching freeganism probably should have changed his life more than it did. But its difficult, and there are always questions of degrees of success living in a certain way.

“To want not is an incredible difficult thing to achieve,” he concludes.