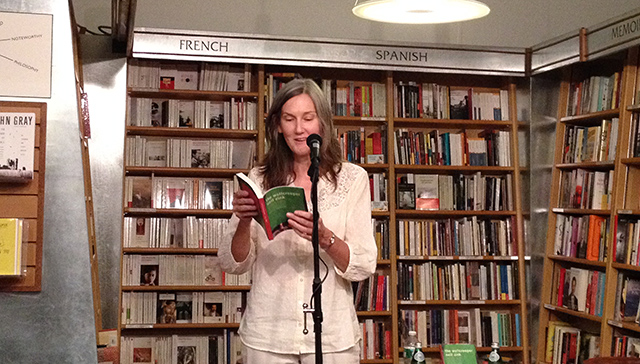

Four years ago, Nell Zink wrote an email to Jonathan Franzen. Franzen responded, and soon they found themselves enthralled with a long distance email correspondence. Franzen is the reason Nell Zink is at McNally Jackson Books releasing her debut novel. He convinced her to turn her writings into a manuscript, The Wallcreepers, and to try and have it published.

A Wallcreeper is a small mountain bird found in Eurasia and the anchor of Zink’s novel that binds Stephen and Tiff. N+1 excerpted a portion of the novel in Issue 20, and its the same section Zink read at McNally, a humorous and quirky text.

Franzen begins by saying that Zink’s initial email to him was written with a kind of bravado that suggested he should know who she was, even if he didn’t. He wanted to know more. He says she didn’t know much about birds, but she sure liked them alot. Soon her correspondence had blossomed into thousand word letters.

Zink says that parents tend to promote reading as an activity because they love nothing more than a child sitting quietly entertaining herself. Her parents in particular seemed to like this. By kindergarten, she was writing her own stories, many about a purple kangaroo. For her, the act of taking her writing more seriously was a progressive progress that is still evolving.

One of her later projects featured a diatom floating along ocean currents. She was a teenager. The diatom would embark on an epic adventure traveling the sea. Eventually the diatom would come across pelagic sediment–essentially a mass grave of other diatoms, and be forced to confront the reality of death as it continued floating through the ocean. “At nineteen, I saw this novel as my life’s work,” she says, but adds, “I never got very far in his adventures.”

To get people to identify with a character, Zink says, its better if they know very little about them. Diatoms are perfect for that kind relatability. She points to the popularity of the smiley face as an example of a character that people love but who they have very little knowledge of.

Zink has lived in a number of places and held various careers. As a result, she’s been called a bohemian.

“I was married to all sorts of people–the sort of thing one does as a young person.”

The important thing was creating enough time and space in her life to have surplus to create and write. She cares about art and the creative act, not the commercial components of creativity. She’s critical of New York City, for instance, because too many people “come to succeed and make money.”

For a while, she self-published a music zine. Unlike today, she says, there was more of a stigma attached to self-publication. She had about thirty regular subscribers, and maybe would print a run of a hundred at a time. She was always amazed when musicians would ask her to write about them as if they thought she was hugely influential or had a huge circulation. On the other hand, they would give her CDs and sometimes she could sell the discs for a few dollars each. In one issue of the zine, Zink also included a story about an alcoholic diatom.

Zink lives in Germany now, and speaks fluent German. She often translates technical documents.

“I feel like everyone has a strange story about how they learn German,” Franzen says.

In Zink’s case, she had a boyfriend who wanted to tour Germany. She was a sophomore in college but went anyway. The boyfriend left, but Zink, refusing to depart without at least knowing German, committed.

In high school, Zink joined the track team. After the first week, she decided she hated it. Her mother wouldn’t allow her to quit though, and she ended up faster than the other girls on the team who actually wanted to be there. She says it didn’t make her very popular.

“Its important to be hated in high school. It makes for better writing later,” Franzen says.

Zink found her ideal reader several years ago in the Israeli novelist Avner Shats. She describes Shats as her “best pal.” She only really wanted to write for him. She says though that she found reading one of his novels difficult, and ended up writing a novel about what she imagined Shats’s novel was about.

Shats was the only person Zink wanted to read her novels and she never saw publishing as necessary since she could simply forward him a copy of what she had written. Eventually of course, she came around to the idea of publishing in part because of Franzen. She writes emails regularly to both authors but says to each, she has a different authorial voice. Franzen for instance, knows many American idioms that would be odd for Shats.

“If you have money, you can afford to read,” Zink says. She grew up reading Virginia Woolf, an author her mother would give her. “I was raised in books by women,” she says. She adds, “The canon wasn’t swarming with women.”

Her main take away from Woolf was that she shouldn’t write for money. Other types of work could pays bills and allowing her to read and write. She’s much more interested in art for art’s sake. Money always influences art, and even when its not just about money, changing the audience influences what she writes. Knowing her book was being published inevitably altered it.

Zink sees a generational difference between writers today and in the past. She reflects on a time when writers had small coteries and created something and their small group critiqued it. Now there is much wider audiences. And now artists expect to win prizes.

Still, even earning wide recognition is limited. She had some concerns the first time her writing was publish in N+1 that she would attract a lot of criticism. “Now I’ve realized there aren’t THAT many people paying attention.”

Nell Zink and Jonathan Franzen

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

McNally Jackson Books