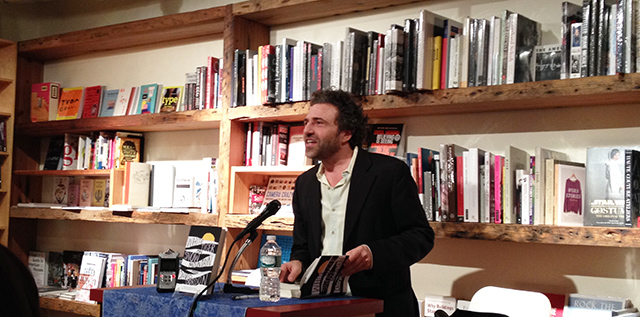

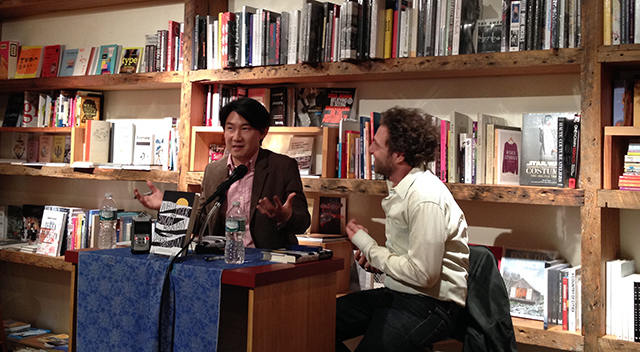

David Gordon’s newest collection of stories, White Tiger on Snow Mountain, blurs the distinction between fiction and biography. Released last week, he spoke with Ed Park, founding editor of The Believer and the editor that brought Gordon’s collection to life, at BookCourt in Brooklyn.

The stories in the collection are the product of narratives written over the course of many years. Gordon even wrote a novel in between the first story and the last, meaning they draw inspiration from a wide period of time, and ultimately making the collection a broad reflection of Gordon as a writer.

Some of the stories include fantasy and horror elements, though Gordon sees these influences are subtle. In some instances, the sense of horror comes from invisible or unseen characters. These are people who may or may not exist, and that uncertainty strikes Gordon as a horror element.

The collection is dominated by a novella length story, one that he spent years honing. He shared the story with his friend Rivka Galchen, who told him it was the best thing he’d written. He ended up cutting quite a bit from the story. “I was just trying to balance it in terms of tone,” he explains.

Gordon spends a lot of time considering the balance of four elements of a story. He explains that he uses a matrix like system to ensure the correct proportions. He cites as an example funny versus sadness. As a story becomes more sad, he also must make it more funny. If it becomes uglier, he has to add beauty. The precise rubric is still secret–Gordon says he looks at the chart so often he forgets what exactly he is balancing. He keeps a chalkboard wall in his home with notes.

He says he is always pushing beyond what he has already written. He always wants to write something new. “I’m always literally on page one.”

Gordon has written both novels and short stories. He doesn’t see much difference between their construction, but he says he always feels like he knows which form he’s working on. The main difference for him is that stories are little things that he can “rotate” in his head. A novel is different in its size and scope–he describes it like having directions to get somewhere and still not really knowing where he is going. However, with both forms, he is always moving towards a goal.

“Often I have the ending,” he says. From there he makes micro adjustments.

He spent a lot of time agonizing over the title of Hawk. He would make changes in the middle of the night, then revert back again. “If I can can change this so easily, does it really matter?” he finally concluded.

“I start with simple the things,” he says, and that ultimately all the characters are versions of him, or at least start out that way. They might do something mundane, and then they evolve into a story from that point. “I’m not the kind of writer who is going to do a lot of research.”

“The more I’m trying to dream myself into the story, the more the person becomes not me,” he says.

He adds that a great editor fixes things that a writer can’t ultimately figure out. Sometimes editors are really good at cutting things.

“Sometimes very late in the process I’m make major changes.”

He’s also working on a new book, a romantic sex story that is a combination of science fiction and spy mystery with clones and art thieves. “The more I say it, the worse it sounds,” he says.

David Gordon and Ed Park

Monday, October 27, 2014

BookCourt