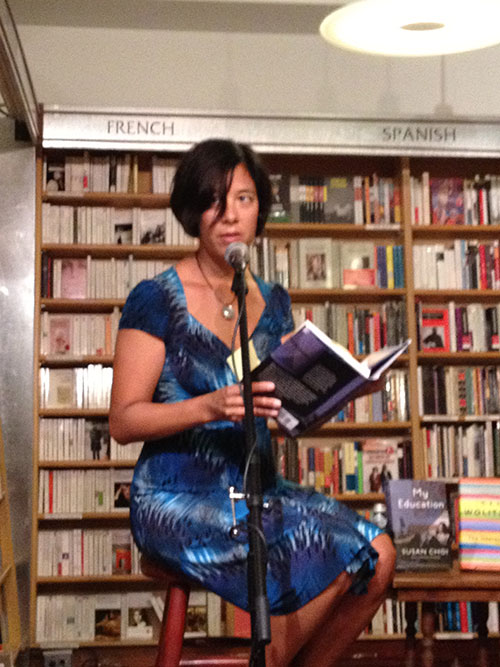

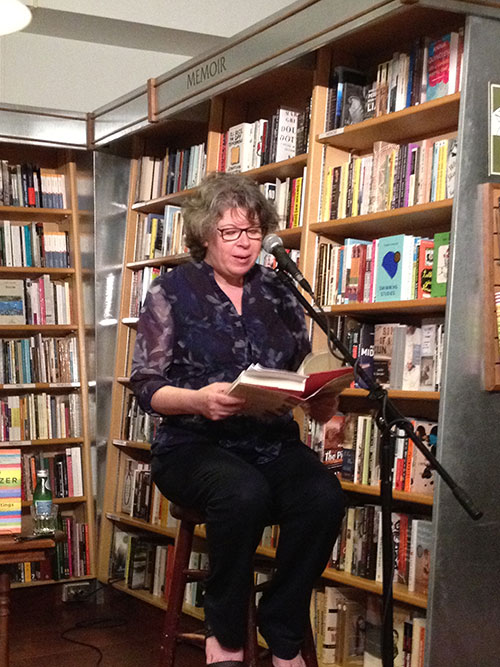

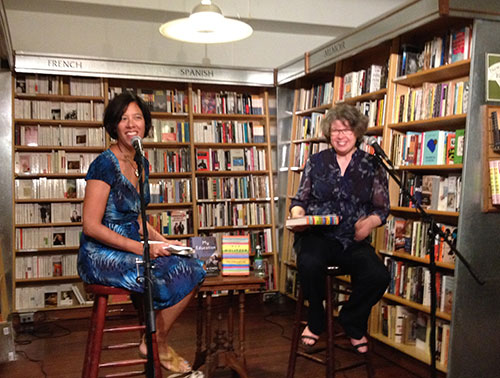

McNally Jackson Books hosted authors Meg Wolitzer (The Interestings) and Susan Choi (My Education) to read from their latest novels and discuss their books and writing craft.

Choi and Wolitzer met for the first time that evening. Both lavished praise on the other. Wolitzer’s novel, The Interestings, traverses multiple periods in the lives of two couples, with one couple finding wild, unexpected success. Choi describes how she perceives The Interestings as a story about envy and asks Wolitzer if she intended it that way.

Envy was the starting point–the way for her to enter the novel. Depictions of envy on television and in film are manipulated and grossly exaggerated, Wolitzer says, and those mediums never delve into the intimate moments of envy between friends, the casual envy of small successes.

By contrast, Choi’s book, Wolitzer says, is not about envy but instead the idea of desire. My Education follows the story of a young woman having an affair with an older professor, a child produced from the relationship and then a great chronological leap forward examining mature characters.

Desire is important, but for Choi, her novel developed from a desire to explore youthfulness, a period she believes she has finally moved away from. She begins jokingly about the horribleness of publishing contracts. She had sold an unwritten manuscript, and then had to produce the book to fulfill the contract. She was unhappy with the results of that attempt, but stuck with the idea of youth as the driving force of the narrative.

Choi is shy of saying she has gained wisdom over the years. She suggests a fear of confronting those claims ten or fifteen years from now, then having achieved real wisdom and having realized how little she currently possesses. But something has changed for her. The big moment is children: “my maturity didn’t start until having kids.” [pullquote]“my maturity didn’t start until having kids.”[/pullquote]

In her youth, she was oblivious to children. In a way, she didn’t even realize then how oblivious she was, saying, “I didn’t know I didn’t care.” But she wanted to write about a woman who hadn’t yet passed into that phase of adulthood–and the result is that throughout her text, the character ignores the presence of her baby. Youth blinds the character.

Both books confront issues pertaining to chronology, an important component of narrative structure. Wolitzer’s novel transitions between multiple periods in the characters’ lives. She accomplishes it seamlessly, Choi praises. But Choi’s book unfolds more linearly with an intentional great leap forward flashing ahead into a present years from the novel’s opening.

Wolitzer sees the fluid relationship with time as necessary to strong narratives. “Flashback is a false construct,” she says, explaining that in real life we don’t experience distinct flashes of our past, but instead our relationship with time is more mutable and indistinct. Nobody sits around thinking about the past in a vacuum from the present.

Capturing that essential ambiguity in time is difficult though. She relies on narrative tricks to control time, citing a sentence in her book, and then explaining: “why have wistfulness unless time is going to pass?” Its meant to hint to the reader the narrative’s interest in the future, with the passage of time. The author can clue in the reader with hints to help guide them as they navigate the text.

Choi intentionally took another approach. She wanted a big hard leap in the middle of her narrative. Later, after having written it, her editor insisted on softening the blow to the reader’s frame of reference.

Despite differences in narrative time, both authors agree in the importance of writing novels in page-order. Its a mistake Choi made in her early novels, she explains, and wished she had figured out sooner: writing out of page-order disrupts the flow of the text. Her first two novels she admits were written as scenes and then stitched together later. [pullquote]“I want to experience what the reader experiences.”[/pullquote]

Wolitzer explains: “I want to experience what the reader experiences.” It takes patience to write in page-order but ultimately keeps the novel organized and helps keep the story together.

The discussion shifts towards the fear of embarrassment. Since readers often superimpose the author onto the characters of a novel or make an assumption of autobiographical characters. Both women agree that drawing on personal experience is an important part of writing, but often readers confuse the moments that are inspired by autobiographical events. Choi says she felt the character she most similar to herself is a septuagenarian man from her previous novel. Readers never ascribe her to him because of differences in age and gender.

But though writing about intimate personal moments can lead to embarrassment afterward, writers shouldn’t let that interfere with the text. “I think when you’re writing, you live in the book,” Choi says, meaning authors are too caught up in the story to worry about consequences or embarrassment in the moment, but later she becomes conscious of what she’s publishing and she worries.

Particularly salient to this point is Choi’s sex scenes. She is preoccupied now with the fear of judgment from the parents at her childrens’ school. Still, she wanted to write sex scenes accurately–sex is funny and awkward, and she wanted to capture that. She cites Francisco Goldman’s novel, The Ordinary Seaman, as an example of what she aspired to.

Wolitzer follows up by saying that writers need to work in a safe place to allow creativity to evolve. She describes the internet world as “instant intimacy,” and reflects a discomfort with the way people interact and react on the web. She adds that she doesn’t like crafting characters based on people she knows– she enjoys creating characters. [pullquote]“I think about likeability a lot because I write characters people don’t like.”[/pullquote]

Choi agrees saying “character is the most important thing.” Characters are what readers remember. “I think about likeability a lot because I write characters people don’t like.” However, she also thinks sometimes readers complain about disliking characters because of some other kind of fundamental flaw in a text. Unlikeable characters are an easy way of describing a more intangible problem.

“You have to want to be in that world,” Wolitzer says in regards to crafting a compelling narrative. And that’s why writing humor into novels–she cites Philip Roth as an example–is important in connecting readers to the characters.

Susan Choi attended a an MFA program shortly after graduating from college. Part of her regrets attending some soon after graduating, but like many newly minted adults, was driven by fear. “I was really scared when I got out of college,” she said, and she worried about paying off her student loans immediately, “I didn’t have adventures.”

Choi also found workshops intimidating. Writing for a reader was motivational, but “the MFA was was writing for a committee,” and she always had some “sense you need to please everyone. I was never clear how to deal with the workshop.” Still, she praises her former classmates as great writers. Ultimately it was about learning who to ignore, a process that she tries instilling in her students in the workshops she teaches now.

Wolitzer adds that as writers mature, the process becomes easier because “you know that you are right more often.”