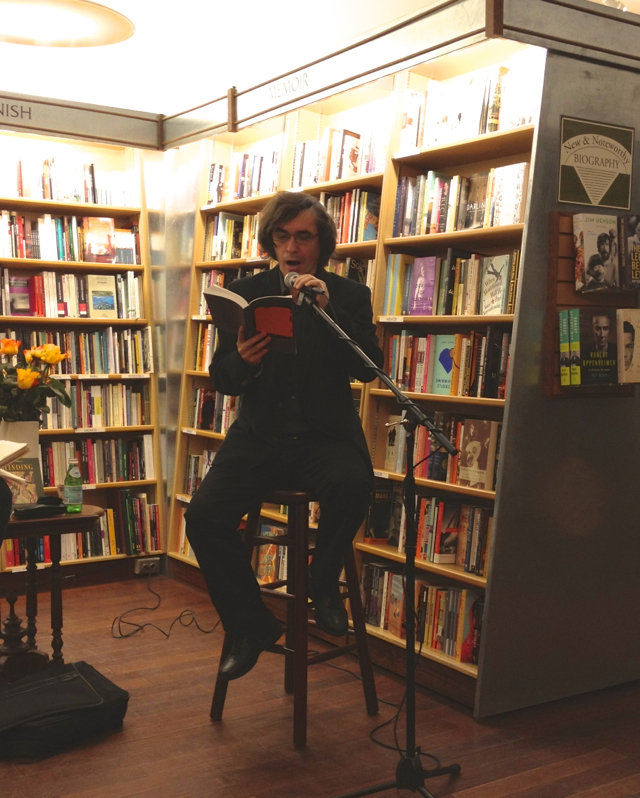

McNally Jackson Books served as the last stop on the American book tour for Romanian author Mircea Cărtărescu as he celebrated the release of the English translation of Blinding, a novel described as dream-memoir. He was joined by Joshua Cohen, author of Witz (2010) and Four New Messages (2012).

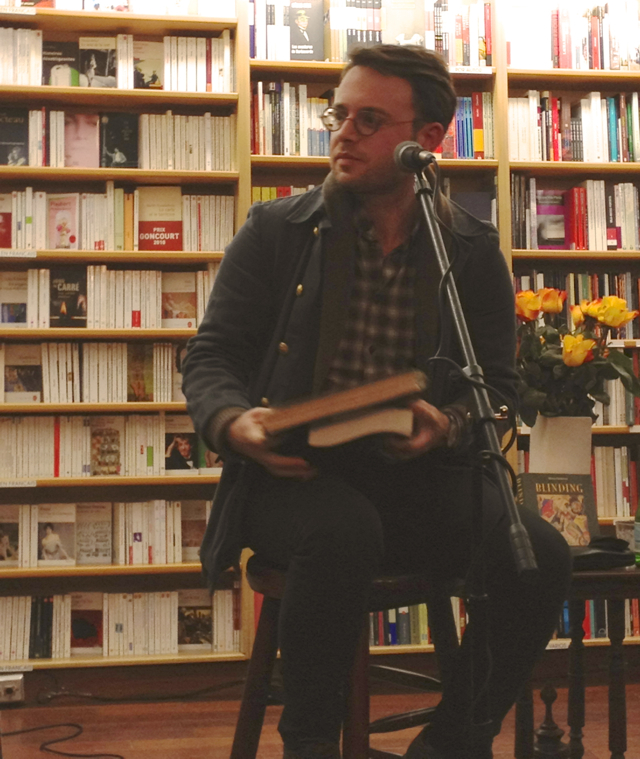

Cărtărescu read first from the original Romanian text followed by Cohen reading the translation in English. Cohen then lead the discussion.

Cohen asks about the the epic nature of the book, the first in a trilogy that Cărtărescu spent the last fifteen years writing. But Cărtărescu is quick to correct him; its a book that took a lifetime of writing. “I suddenly felt the need to do something… for myself, like a huge sculpture in front of a building.”

[pullquote]”I started writing a crazy book without any limits or consequences.” [/pullquote]

Cărtărescu’s first four books were written when Romania was still a member of the Soviet Union. His career began with poetry. The size of this project was different than his earlier works though. With Blinging, he set out to do something different. “I started writing a crazy book without any limits or consequences.”

The length of the book was important too. He wanted something long and epic. “The thickness of a book is stylistic,” he explains. (Joshua Cohen is no stranger to length books. Witz is a hefty book.) Cărtărescu elaborates saying he didn’t just want a long manuscript; he wanted a project that would carry him through a long period of time, something that would keep him occupied. “Ideally I would have written a book for my whole lifetime,” he says.

Bucharest serves as a major component for Cărtărescu’s writing, and often readers insist he has captured the city down to specific buildings and specific streets. Cohen inquires about how much of this is true, about the importance of cities to books.

The city is a false one, Cărtărescu says, the city is an invention.

In the Soviet era, rural peasants like his parents found themselves relocated to urban centers to become factory workers. Within the city, they lived within a small ghetto with other similar peasants. Cărtărescu described the neighborhood as their own little village he never needed to leave. He first entered the center of Bucharest at the age of twenty, having never left his ghetto of the city before then. He compared the area to the Bermuda triangle, defined by the three cinema’s he and his parents would visit. So he insists he does not know Bucharest well.

[pullquote]”The streets and buildings were sculpted in my brain,” [/pullquote]

A city is not a combination of buildings, he says, its a state of mind. Writers always appropriate their own cities and reinvent them as they need to. The Bucharest of his books served the needs of the book without getting hung up on reality. “The streets and buildings were sculpted in my brain,” he explains.

Cohen moves on asking about the culture of Bucharest, suggesting that much of it was destroyed in the Soviet era. Cărtărescu agrees that under the Stalinist era, the old culture of the city was razed. But after that — by the 1960s — writers and poets were back and writing. There were of course limits: “We were all in a big cage and the tiger was facing us.”

He published four books before the fall, and all four he stands by now. After the fall of the Soviet Union, his own writing remained the same. “The revolution is not enough to change my style,” he jokes. Cohen points out though that Cărtărescu is now writing prose even though he started out as a poet.

[pullquote]”Poetry is a strange word and it doesn’t mean one thing,”[/pullquote]

“Poetry is a strange word and it doesn’t mean one thing,” Cărtărescu corrects. “I’m not interested in writing verses.”

“Poetry is fundamental to the world, a way of seeing the world,” Cărtărescu continues. To him, poetry serves not as a form of words by an idea of perception. His prose is no less a poem in this sense. Instead, poetry strikes him as simply a way of capturing and explaining the world. He describes how a poet sees the world in a different way than everyone else; an ordinary person looks at an object from the front and that is all, but a poet will take the time to look at that object from a new or different angle, from above, or from below.

Cărtărescu wrote out the novel by hand in journals. He claims he made no mistakes and removed none of the pages. “My manuscript is absolutely clean.” Yet, there are multiple layers to the story — the challenge Cărtărescu, explains, was balancing them all as he wrote, juggling ten different ideas at once.

Also in writing the manuscript, Cărtărescu is not particularly worried about the verisimilitude of facts or history, only the essence. He draws from memories as much as from history books. If in some of his inventions, he is wrong, he accepts those mistakes. He says that the splendor of the facts are far more important to him than their accuracy. Still, he insists everyone should read books of facts and learn about the world around them.

Cărtărescu has been reading a lot lately on mathematics, especially the history of mathematics, for a new book he is working on. The book is meant to address the question of whether we can escape our world and our time. He describes the concept of the fourth dimension. He explains it as a core covered by the third dimension like wrapping paper. He imagines this place as a kind of paradise.

A member of the audience asks about the importance of the Romanian language to the text. Cărtărescu explains that most of the book was written while he was abroad, either on grants or teaching at other European universities. To him it is independent of Romania.

However, he also explains, using an analogy of the American middle west. He says that artists born in the midwest have to run away to find success. Romania is like this in that it is not a place where writers become famous. The centers of validation have always been places like Paris, London, and New York.

“I have a need to be validated–by myself. Its nonsense to be validated by others,” he says. “My first reader is always myself, and my most harsh critic.”