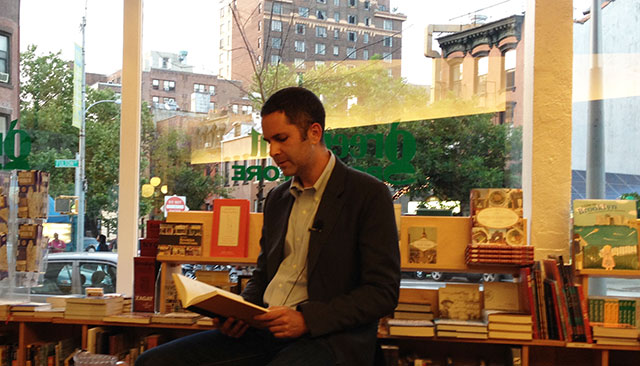

Tom Rachman began his career as a journalist, but his true desire was always to write fiction. His debut novel, The Imperfectionists (2010), perhaps unsurprisingly, told the story of decline of a once great newspaper. The Rise & Fall of Great Powers shifts settings from a newspaper office to a bookstore, another cultural spaced threatened by modernity.Rachman read from the new novel at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn and discussed it with his Random House editor, Susan Kamil.

The Rise & Fall of Great Powers follows bookstore clerk Tooly Zylberberg as she discovers her past, an unexplained period in her life as she traveled the world with strange people. The novel follows three distinct timelines– a present while Tooly is in her thirties, a past of the late 1990s when Tooly was in her twenties, and a 1980s past when she was a child. Each of these are interwoven to allow the reader to discover Tooly’s story alongside her.

Tooly works in a bookstore where she mostly spends her time reading books. Rachman says he wanted the setting as an excuse to spend a year or two in a bookstore. He enjoyed writing about setting and adding the details. He claims an unhealthy obsession with books. When he moves, which is often, they are the first thing he unpacks. He says each copy of a book offers some kind of memory attached to it.

The Imperfectionists grapples with a declining newspaper industry, but he sees this as a different problem than the one facing books. Periodicals play a different role in society. They are more disposable, and perhaps more malleable to form. Books on the other hand, aspire to longevity.

Tooly, surrounded by piles of books, feels skittish around computers and people. But she’s here hiding out from her life and a childhood that is a mystery. Its a puzzle she wants to solve. At the core, The Rise & Fall of Great Powers is a mystery. Rachman is clear though this is not a mystery book. “Its not a genre book,” he says. “The mystery in this book is her.” If it is a mystery book, its a self-aware, with one character saying to Tooly just that.

The book is filled with many characters. There is Humphrey, a crazed and curmudgeonly old Russian– Rachman reads his dialogue with a surprisingly strong accent–Sarah, a temptress luring Tooly to adventures, and others seep in. They are described as Dickensonian, and intentionally so. Rachman, like his protagonist, Tooly, is fascinated by Charles Dickens. She Tooly a lot. As a child, books offered her an escape and partly she’s hoping for a Dickensonian character to whisk her away from her horrors.

Rachman sees his novel as dealing with a change. People are under the misconception that they have a fundamental way about themselves and that they are not changing who they are. He says that because people change so slowly they never see it happening. Their belief is that the world is changing around them, rather than that they themselves are changing. The gaps in Tooly’s life are meant to create a better sense of this evolution by highlighting distinctions rather than through incremental differences that are rarely observed. Rachman also wanted to confront the changes in society over the last three decades, and splitting the narrative between these three timelines allowed him to do just that.

He also wanted to deal with the idea of what it meant to have a friendship. Is kindness enough to entitle someone to friendship or is it condescending to befriend someone simply because they once showed a kindness? Conditional relationships require someone to be a friend because they want to, not because of an unspoken contract. Rachman says the character Benn is meant to deal with this issue. It represents a kind of selfishness, he says, that was very popular in the 1990s right up until 2008.

Like Tooly, Rachman spent much of his life traveling. He never felt like he had much of a single nationality or a singular place to belong. When he was beginning to write, he developed an anxiety over the sense of place. Great writers all seem to have written to specific places. They had geography as something they wholly understood. But for him, he had no place.

He started a career in journalism. He would have preferred fiction, but journalism paid. He found journalism valuable for its technical side. No job in fiction could offer the same opportunity to work with the volume of words as a journalist. Journalism also produced a strong sense of audience. He says that knowing who the reader has value because its a way of crafting something of value for the reader.

Writing was something he had to work out. He never went for a creative writing degree, saying “I just figured it out through writing.” And he wrote a lot. At one point near his thirtieth birthday, he quit his job as a correspondent in Rome and moved to Paris intending to write a novel. He had saved enough money to live for a year. He assumed that a year would be plenty of time to write a novel.

Nine months later he hadn’t finished writing it. He hadn’t written very much of it at all. He decided there was a solution: a novel, at three hundred pages, could be finished in thirty days if he just wrote ten pages a day. He finished that draft in a month.

It was awful, he says.

Broke, he went back to work in journalism. He says that first horrific manuscript was his creative writing program. His next script would be better. Still, he had come to respect the idea that 400 words was very different than 100,000.

He took up better discipline, something he believes is essential. He applied the things he learned from the year writing the awful novel, and he set out on a new manuscript. He wrote it out until he had a finished story. That one wasn’t great either, at least until he started revising it.

“Revision is almost everything,” he says.

He explains that there is a temptation to look back at work as its written, but it is unsettling to look back at writing that hasn’t been revised. Its discouraging. He finds it better to write out the whole story first and then revise from there.

The Rise & Fall of Great Powers took a year to write a terrible first draft. It was not the book he had set out to write, and he tossed that entire manuscript. He spent another year writing a new first draft from scratch. By then he was committed to seeing it through. He wasn’t going to start over again. So he set to editing and revising.

Rachman likes to work with an outline, but he warns about sketching out too much detail. Scenes where the author doesn’t have spontaneity never seem as real as scenes where the writer suffers emotionally. He says this about modeling characters on real people. Snagging aspects of people is a great way to character build, but modeling a character wholesale on someone only ever leads to dead characters.